Living in the land of martyrs

Kristina Glicksman

Friday, May 3, 2019

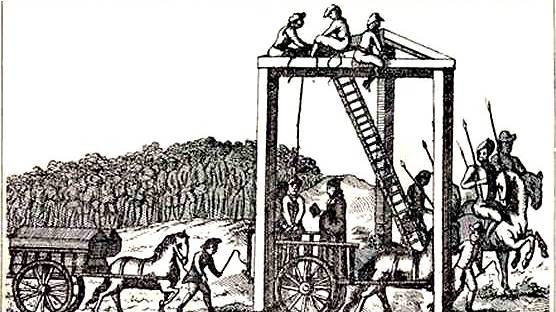

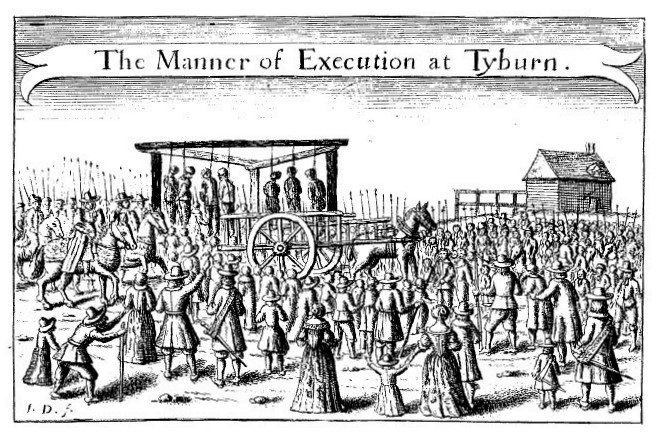

The gallows at Tyburn, where many martyrs were executed during the English Reformation. Illustration circa 1680. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Faith of our Fathers! living still In spite of dungeon, fire, and sword: Oh, how our hearts beat high with joy Whene'er we hear that glorious word.

Faith of our Fathers! Holy Faith! We will be true to thee till death.

This hymn has always been a favourite of mine. As a child who was always partial to an adventure story, especially if it involved swords, there was always something exciting about this particular hymn which was lacking in some of my other childhood favourites, like “Let There Be Peace on Earth”. But whereas words like “let it begin with me” represented a goal to strive for, “we will be true to thee till death” was a concept so far removed from my comfortable, middle class, American existence that it seemed to belong more to that same realm of heroic fantasy as the story books. Of course I knew of the martyrs of the early Church, but they were also stories that belonged to a different reality. To my limited experience of life, they had no immediacy. “Dungeon, fire, and sword” to me were a poetic allusion to adversity. I never thought to ask: “Which dungeon? What fire? Whose sword?” Until I lived in England. There I found a kind of Catholicism I had never encountered at home. The best words I can think to describe it are fierce and proud – in the best sense that those words can convey. It was the first and only time in my life that I heard someone express in all seriousness her ambition to be a martyr.Our Fathers, chained in prisons dark, Were still in heart and conscience free: How sweet would be their children’s fate, If they, like them, could die for thee!

I began to learn about the persecution of Catholics under Elizabeth I, when there were men known as priest hunters, who earned their living by searching for Catholic priests and running them to ground, arresting them and handing them over for torture and execution as traitors. I learned about Catholic families who sent their sons to be educated on the Continent and of brave young Englishmen who entered the Society of Jesus and/or studied at the English College in Rome, where they were regularly greeted by St. Philip Neri with the words: “Hail, flowers of the martyrs!” The average life expectancy of a Catholic priest entering England at that time was less than a year. And still they came.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

May 4: Feast of the English Martyrs

Many of those who suffered during this period and who offered up the ultimate sacrifice have been officially recognized by the Catholic Church over the years through beatification and canonization: 284 in all, each commemorated on a specific day (often the anniversary of their death). But every year on the 4th of May, they are remembered together, and their witness of faith along with that of many, many others whose names have not been recorded is honoured in the celebration of the Feast of the English Martyrs. The entry in the National Calendar for England reads:The English Men and Women martyred for the Catholic Faith 1535–1680 and beatified or canonised by the Holy See. On this day in 1535 there died at Tyburn three Carthusian monks, the first of many martyrs, Catholic and Protestant, of the English reformation. Of these martyrs, forty two have been canonised and a further two hundred and forty two declared blessed, but the number of those who died on the scaffold, perished in prison, or suffered harsh persecution for their faith in the course of a century and a half cannot now be reckoned. They came from every walk of life; there are among them rich and poor, married and single, women and men. They are remembered for the example they gave of constancy in their faith, and courage in the face of persecution.I never knew of this feast until I happened one day, quite unintentionally, to attend Mass at the Oxford Oratory on May 4th. We sang “Faith of Our Fathers” as I had done so many times before at home, but this time the words shook me. This time I understood what they were about. I understood that this was a hymn about the survival of the Catholic faith in England. I wondered how many people around me were singing “faith of our fathers” and not meaning, as I did, our fathers in faith, but actual personal ancestors, being able to trace their Catholic heritage with pride to families who had retained their faith in the face of intense persecution. And I admit I envied them. Because they had something I did not have. Because these brave and holy men and women belonged to them in a way in which they could never belong to me. But living there, surrounded by the spirit of English Catholicism and by constant reminders of its past, I could not help being drawn in. Even if these saints could not be my family, I could still claim them as friends. After nearly nine years living in England, I have dozens of examples of encounters with these saints. Some, like St. Thomas More and St. Edmund Campion, are famous even beyond their native land. But I would like to take this opportunity to introduce you to three of my friends who are less well known outside England:

St. Ralph Sherwin

On the wall outside the St. Thomas More Chapel in the Oxford University Catholic Chaplaincy there is (or at least, there was) a long list of Oxford alumni who were also Catholic martyrs – listed according to college. Under my own college, Exeter, there was only one name: Ralph Sherwin, first martyr of the English College in Rome. Though less famous than his friend and companion in death, St. Edmund Campion, his short life of ministry was no less heroic, his imprisonment and death no less brutal. After landing in England under cover of darkness, he spent three months travelling in disguise to preach and minister to Catholic families across the country before being arrested, imprisoned, and tortured. As he was hanged, drawn, and quartered (the standard sentence for treason), his last words were: Jesu, Jesu, Jesu, esto mihi Jesus [Jesus, Jesus, Jesus, be to me a Jesus (i.e. a saviour)]!

Source: Wikimedia Commons/RioVerde

St. Margaret Clitherow

I once paid a visit to the beautiful and atmospheric city of York in the north of England. Walking down that famous medieval street known as the Shambles, I happened upon a small house which identified itself as the house of St. Margaret Clitherow – one of many inspiring examples of the courage of ordinary laypeople. Although fined and imprisoned for not attending Protestant services, she maintained her Catholic faith. Then, in 1586, she was arrested for the crime of harbouring a Catholic priest – a treasonable offence in those days. St. Margaret was aware that if her case went to trial, it was likely that her friends and family, including her children, would be called upon to give evidence. Not wanting to expose others to this risk to their souls, she refused to enter a plea. At that time in England, the punishment for refusing to plead was peine forte et dure. She was laid, face up, across a small, sharp stone, and the door from her house was placed on top of her and piled with large rocks until the weight caused her back to break. What a privilege it was not only to visit the house of this brave woman but to attend Mass where it had been celebrated by people who knew they were risking their very lives in doing so!St. Nicholas Owen

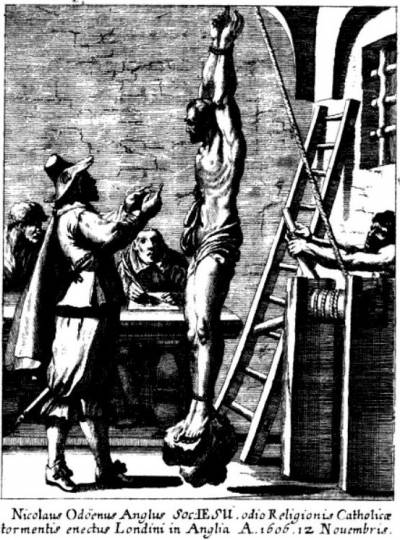

But my favourite of all the English saints is ever and always St. Nicholas Owen. I love him because he was a layperson and a simple man who served God in the practice of his trade. A carpenter and a Jesuit lay brother, he travelled up and down the country visiting Catholic houses and single-handedly building ingenious hiding places in which priests could evade detection when the priest hunters came banging on the door. Just before I left England, I fulfilled a desire of many years when a friend took me to visit Baddesley Clinton, a house of the 16th century in which visitors can see two of these legendary “priest holes”. John Gerard, a Jesuit who survived his time of ministry in England, wrote a fascinating account of his experiences. Time after time he tells of narrow escapes into hiding places and waiting as priest hunters prowled around looking for some sign of his whereabouts and even tearing into walls in search of him. It is said that so ingenious were the design and execution of these hiding places that the priest hunters never discovered a single one that was not betrayed to them by spies or victims of torture. It is also popularly suspected that in some of the houses around England which survive from this time, there may still be “priest holes” that lie as yet undiscovered. When St. Nicholas himself was captured and tortured to death, he told his tormentors nothing, taking to his grave knowledge which, if revealed, could have spelled the end for the practice of the Catholic faith in England.

Engraving depicting the torture and interrogation of St. Nicholas Owen in the Tower of London. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Related Articles:

<<