Deacon-structing receiving Communion, part 3

Deacon Pedro

Monday, August 16, 2021

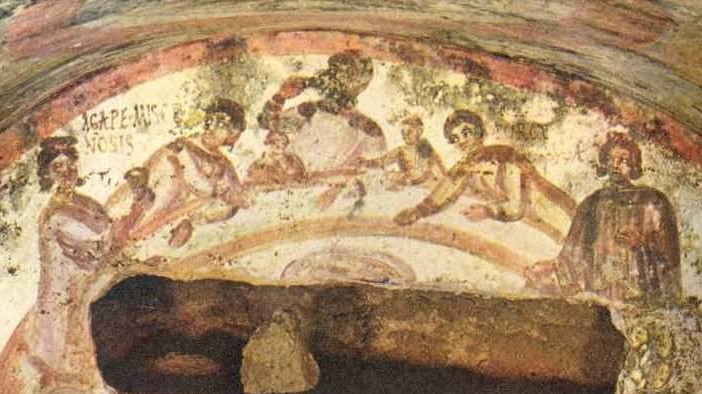

Early Christian depiction of an "agape feast". Fresco of the 4th century from the Catacomb of Saints Marcellinus and Peter in Rome. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Last week and the week before, we reflected a little bit about what it means to receive the Eucharist. We receive because it is Christ himself that we receive. This is why we must receive Communion with deep reverence. I believe that the Apostles and early Christians received with deep reverence. I'm pretty sure that they understood what Jesus meant when he said, “I am living bread” and “Unless you eat this bread” and “This food is my flesh” (see John chapter 6).

Of course, there are no written accounts of those first meals. I can only imagine what was going through the Apostles' heads when Jesus offered them a piece of bread and said, “Take and eat. This is my body.” If I was with Jesus and believed that he was the Messiah, even if I did not fully understand and he gave me something to eat, telling me it was himself I was consuming, I think I would do what he asked with some reverence. Having heard him say, “Do this in memory of me,” would mean that I would remember that first moment when I continued to do it in memory of him.

Every week, Deacon Pedro takes a particular topic apart, not so much to explore or explain the subject to its fullness, but rather to provide insights that will deepen our understanding of the subject. And don’t worry, at the end of the day he always puts the pieces back together. There are no limits to deaconstructing: Write to him and ask any questions about the faith or Church teaching: [email protected]

Every week, Deacon Pedro takes a particular topic apart, not so much to explore or explain the subject to its fullness, but rather to provide insights that will deepen our understanding of the subject. And don’t worry, at the end of the day he always puts the pieces back together. There are no limits to deaconstructing: Write to him and ask any questions about the faith or Church teaching: [email protected]

I suspect that this was the case for as long as the Apostles were presiding over these meals.

But I can also understand how, little by little, some of that reverence and awe would have been lost. The earliest writing we have on the practice of receiving Communion is a disputed text from St. Cyril of Jerusalem (meaning some scholars think he didn't write it and some think he did) from the 4th century, which says:"When you approach, take care not to do so with your hand stretched out and your fingers open or apart, but rather place your left hand as a throne beneath your right, as befits one who is about to receive the King. Then receive him, taking care that nothing is lost.” (Catechetical Lecture 23 "On the Sacred Liturgy and Communion")There is no reference on how to receive Communion in any writings before the 4th century. We know from St. Paul that the Corinthians would gather for their weekly “breaking of the bread” and were bringing their own food (1 Corinthians 11:17-34). We also know from Ignatius of Antioch’s Letter to the Smyrnaeans (AD 110) and from Tertullian's Apology for the Christians (AD 197) that in some places, these weekly gatherings were called “agape meals” or love feasts. For the first 300 years, the Church was persecuted. Early Christians gathered in their homes for the weekly breaking of the bread (see Acts 7:42-47 and 20:7). These early liturgies were based on Jewish Sabbath synagogue gatherings where prayers and Scriptures were read. Sometimes, as many early Christians were Jewish, they would go to the synagogue first and then retire to someone’s home to share the meal. The earliest instruction of the Church, the Didache, describes the communal meal as beginning with prayers over the wine and the bread but says very little about receiving Communion. It does say that those who are not baptized should not receive (chapter 9) and that one should confess their faults before receiving Communion in order to avoid profanation of the Sacrament (chapter 14). We do know from St. Justin Martyr what those liturgies were like. He wrote in his Apologia around 155 AD:

Having ended the prayers, we salute one another with a kiss. There is then brought to the president of the brethren bread and a cup of wine mixed with water; and he taking them, gives praise and glory to the Father of the universe, through the name of the Son and of the Holy Ghost, and offers thanks at considerable length for our being counted worthy to receive these things at His hands. And when he has concluded the prayers and thanksgivings, all the people present express their assent by saying Amen. And when the president has given thanks, and all the people have expressed their assent, those who are called by us deacons give to each of those present to partake of the bread and wine mixed with water over which the thanksgiving was pronounced, and to those who are absent they carry away a portion.It is impossible to know with certainty how Communion was distributed. It is impossible to determine whether people received standing, sitting, or kneeling, whether they passed the Eucharist around, or at what point in history the words of Institution (which were likely recited at every gathering since day one) became formalized as the moment when Consecration occurs. What we do know, from the writings of Ignatius of Antioch, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, and others who wrote in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, is that the Eucharist is the body and blood of Jesus Christ. (For more understanding on how the doctrine of transubstantiation came to be defined, watch Deacon-structing Transubstantiation.) We know that as time passed and the Church grew, there were abuses (as the one St. Paul writes about in 1 Corinthians 11). It is likely that sometime around the 2nd century, Church leaders began formalizing Communion in order to avoid these abuses and to encourage people to receive the Eucharist with reverence. (For example, in AD 325, the Council of Nicaea, in Canon 18, made it clear that only priests were to give the Eucharist to others and not the other way around. Apparently, some deacons were offering the Eucharist to the priests.) In the 4th century, St. Basil wrote that in times of persecution, people without the presence of a priest or minister could communicate themselves, as could hermits in the desert, adding that "at Alexandria and in Egypt, each one of the laity, for the most part, keeps the communion, at his own house, and participates in it when he likes” (Letter 93). I suspect that in order to avoid abuses to the Eucharist, many of the practices of the early Church were discontinued. But it took a few centuries for the new norms to take hold across the Christian world. Come back next week to find out what the Church teaches about how often we should receive Communion and how. - This post is part of a series on Receiving the Eucharist. Read all of them: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

Every week, Deacon Pedro takes a particular topic apart, not so much to explore or explain the subject to its fullness, but rather to provide insights that will deepen our understanding of the subject. And don’t worry, at the end of the day he always puts the pieces back together. There are no limits to deaconstructing: Write to him and ask any questions about the faith or Church teaching: [email protected]

Every week, Deacon Pedro takes a particular topic apart, not so much to explore or explain the subject to its fullness, but rather to provide insights that will deepen our understanding of the subject. And don’t worry, at the end of the day he always puts the pieces back together. There are no limits to deaconstructing: Write to him and ask any questions about the faith or Church teaching: [email protected]Related Articles:

<<