A Quick Take on the New Vatican Document:

What You Need to Know

Allyson Kenny

Thursday, May 17, 2018

CNS Photo/Paul Haring

Today, the Vatican released a new 15-page document on economics and the world financial system, titled Oeconomicae et pecuniariae quaestiones.

I know what you're probably thinking. And you're totally right; this work is highly technical and not for the average “Joe Six-Pack” in the pews.

But never fear. I, a humble Salt+Light associate producer (with a strong academic background in developmental economics), am here with a quick take on what the average Catholic can glean from this document; no economics degree needed, I promise.

And in the spirit of recent Church publications like YOUCAT, I’ve used a question and answer format (and lots of visuals!) to keep things simple and readable.

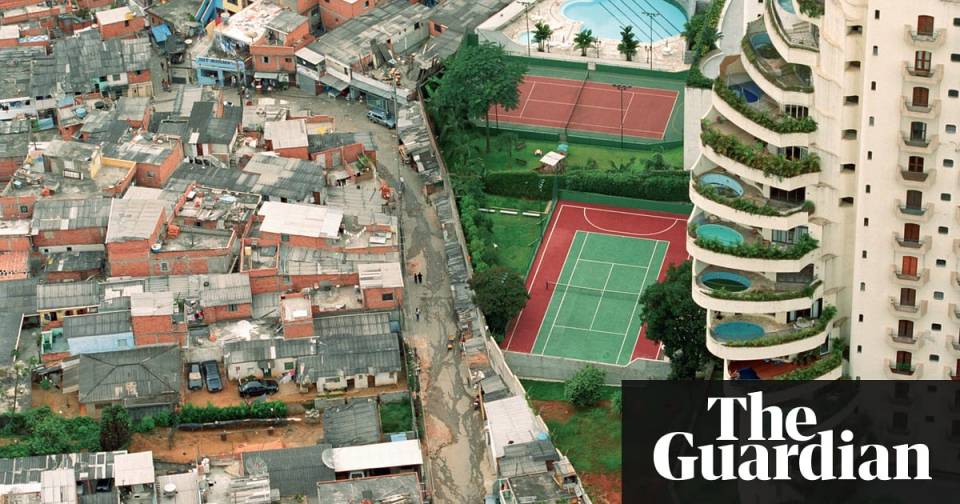

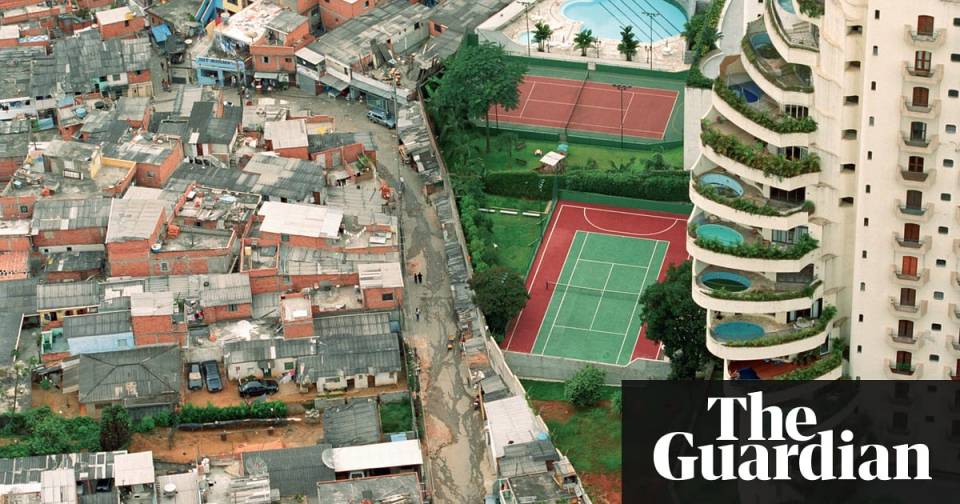

I know the sheer magnitude of numbers like this can be hard to conceptualize, so below I've included my favourite visual representation of this phenomenon. It’s a photograph taken in 2004 in São Paulo, Brazil by Tuca Vieira.

The Paraisópolis slum - without adequate sanitation, waste removal, or even electricity in some cases - sits next to its wealthy neighbour, Morumbi. Note the swimming pool on every corner unit balcony.

I know the sheer magnitude of numbers like this can be hard to conceptualize, so below I've included my favourite visual representation of this phenomenon. It’s a photograph taken in 2004 in São Paulo, Brazil by Tuca Vieira.

The Paraisópolis slum - without adequate sanitation, waste removal, or even electricity in some cases - sits next to its wealthy neighbour, Morumbi. Note the swimming pool on every corner unit balcony.

If we’re all equal before God, with inherent dignity and goodness as His children, we must work towards creating a world that reflects that equality and upholds the dignity of all, not just the rich.

Bring this point home for yourself even further - see how materially rich you are compared to the rest of the world by using this calculator from GivingWhatWeCan.org. Input your country, income, and household members to see where you stand. I was shocked to learn that I grew up in a family in the top 0.1% richest in the world.

If we’re all equal before God, with inherent dignity and goodness as His children, we must work towards creating a world that reflects that equality and upholds the dignity of all, not just the rich.

Bring this point home for yourself even further - see how materially rich you are compared to the rest of the world by using this calculator from GivingWhatWeCan.org. Input your country, income, and household members to see where you stand. I was shocked to learn that I grew up in a family in the top 0.1% richest in the world.

Q: Why is the Church talking about economics and the world financial system?

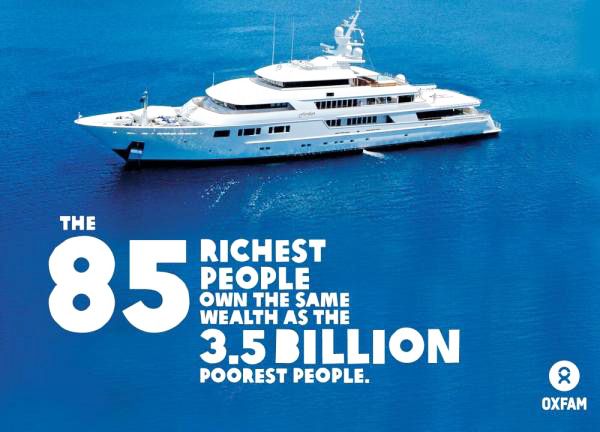

A: Because the world economic and financial system has a stronger influence on the wellbeing of humanity than ever before. While the last 100 years seem to have brought about rapid and unparalleled growth in economic wellbeing for many, inequalities within and among countries (and individuals) have grown. Recent statistics show that 80% of the world’s wealth is held by just 20% of the world’s population. And the number of people living in extreme poverty is still enormous - more than 1.2 billion people live on less than $1.50 USD per day, by the World Bank’s estimate. This should shock and outrage us as Christians.

Source: Oxfam

São Paulo slums - a stark contrast between rich and poor. Photograph by Tuca Vieira.

Q: So what? Why should we care about economics, specifically?

A: Because the Church sets before the world the “ideal of a ‘civilization of love’”, and economics can either be a powerful ally or enemy in creating a world based on that vision. We, as Christians, have an absolutely vital role to play in bringing to fruition a better world. In fact, it’s an essential role of each person’s vocation, and of the vocation of the entire Church both as an ecclesial body, and as the mystical Body of Christ in the midst of our broken world.Q: Okay, so what does this “civilization of love” look like?

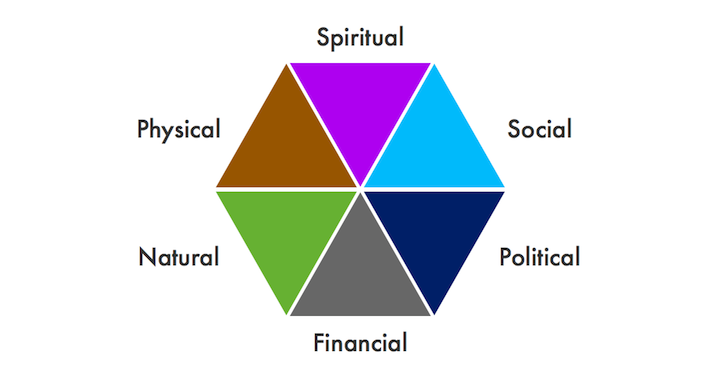

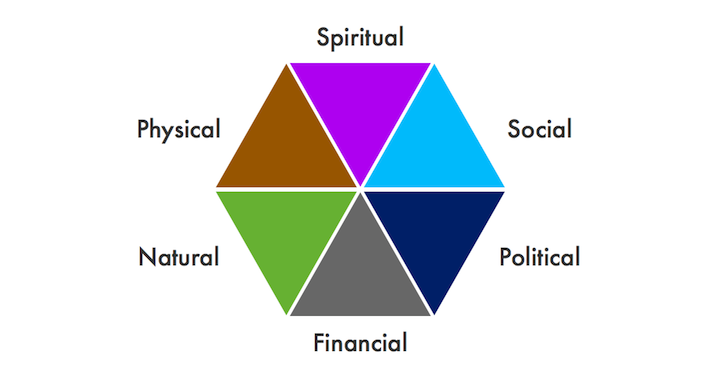

A: It’s a world where all people are able to flourish and prosper, and not just in the economic sense. Here we need to take a holistic view of both individuals and communities. This is often referred to in Catholic Social Teaching as “integral human development” (IHD). IHD is just a fancy, “academic-ese” way of saying that we need to consider all facets of life affecting us - physical, spiritual, mental, financial, political, social, and more - when we think about the ultimate goal of humanity, and the ultimate goal of the Church.

The core facets of integral human development. Source: CAPP-USA.

Q: What does an ethical world financial system look like, according to the Catholic Church?

A:- It must place people before profits. It is centred in and around an ethical and moral understanding of the human person, and is first and foremost for the common good. To add a thought from Laudato Si’, it also must take into account the wellbeing of future generations, and of the Earth itself, not just those living at present.

- Its ultimate goal must be the development of every human person - excluding none - not merely the increase of economic activity. Ever heard of countries being “ranked” by Gross Domestic Product? That’s all about viewing increased economic output as a universally good thing, running completely counter to the sentiment of this document. There is one country in the world, however - the Kingdom of Bhutan - that measures its progress as a nation in a radically different fashion. It’s called Gross National Happiness, and you can find out more about that concept here.

- It must exist within the framework of a “renewed alliance between economic and political parties, where those in power respond of their ‘original vocation as servants of the common good’”. Keep that in mind when voting during your next election - are your political candidates servants of the common good, or only the economically powerful?

- It cannot be a completely “free” market. Certain checks and balances must be implemented upon the market in order to, for example, allow for the basic needs of those unable to take part in the economic system due to disability, mitigate against environmental harm, create a more equitable distribution of wealth, etc.

Q: Wait - so is the Church saying that money, the stock market, or capitalism as a whole is bad?

A: Absolutely not! In fact, the document makes explicit reference to the fact that money is “in itself an instrument of good”, as are “many other things at the disposal of the human person … [as] a means to order one’s freedom and to expand one’s possibilities … likewise, the financial dimension of the business world, focusing the business to the access of money through the gateway of the world of stock exchange, is as such positive.” But, “nevertheless, [these] means can easily turn against the person”. [15] What the Church is asking us, along with political and business leaders of the present and future, is to consider that work has become an “instrument” instead of a good, money an “end” instead of a means, and to recognize that a reckless and amoral “culture of waste” has “marginalized great masses of the population, depriving them of worthy work and leaving them without possibilities, without any means of escape”. We must also consider that the excluded in today’s society are often no longer the “exploited”, but the "leftovers"; those who are placed on the fringes of society because of their inability to participate in the economic system as a whole. Think, for example, of countries in Europe where youth unemployment can run as high as 40%.Q: But what can I do? I’m just one person!

A: Here I’d like to quote from the document’s conclusion at length. In my opinion, it is the most accessible and moving part of the entire work:“In front of the massiveness and pervasiveness of today’s economic-financial systems, we could be tempted to abandon ourselves to cynicism, to think that with our poor forces we can do very little. In reality, every one of us can do so much, especially if one does not remain alone. Numerous associations emerging from civil society represent in this sense a reservoir of consciousness and social responsibility, of which we cannot do without. Today, as never before, we are all called, as sentinels, to watch over genuine life and to make ourselves catalysts of a new social behaviour, shaping our actions to the search for the common good, and establishing it on the sound principles of solidarity and subsidiarity. Every gesture of our liberty, even if it appears fragile and insignificant, if it is really directed towards the authentic good, rests on Him who is the good Lord of history and becomes part of a buoyancy that exceeds our poor forces, uniting indissolubly all the actions of good will in a web that unites heaven and earth, which is a true instrument of the humanization of each person, and the world as a whole. This is all that we need for a living well and for nourishing a hope that may be at the height of our dignity as human persons”. [34]

My suggestions:

Get (righteously) angry at the spread of exclusion and marginalization in our world due to economic forces. Let your anger at injustice fuel action. Invest your own money in organizations that respect Catholic values and environmentally-friendly practices. Think about the moral implications of your work, especially in the secular business world - is your prosperity the cause of others being without - people, whole communities, the planet itself? What concrete steps can you take to mitigate against this? Loss of true economic potential for some often means loss of human potential for all - we are only as strong as our weakest and disempowered brothers and sisters. Place political pressure upon your elected representatives to advocate for the least among us. Join (or start!) parish groups that care about these issues.Finally - what did I leave out?

This document delves into things I am most definitely not going to touch on here, technical concepts like the level of taxation of interests relative to interbank loans (LIBOR), credit default swaps (which were the fuel behind the global economic crisis in 2008), offshore markets, etc. But rest assured that what the Church is saying about all of these things is very rational and sensible - at least in the opinion of those of us who take a common-sense, down-to-earth approach to economics (and to Catholic teaching overall).Related Articles:

>>

SUPPORT LABEL

$50

$100

$150

$250

OTHER AMOUNT

DONATE

Receive our newsletters

Stay Connected

Receive our newsletters

Stay Connected