What we can all learn from Inspector Javert

Kristina Glicksman

Wednesday, July 3, 2019

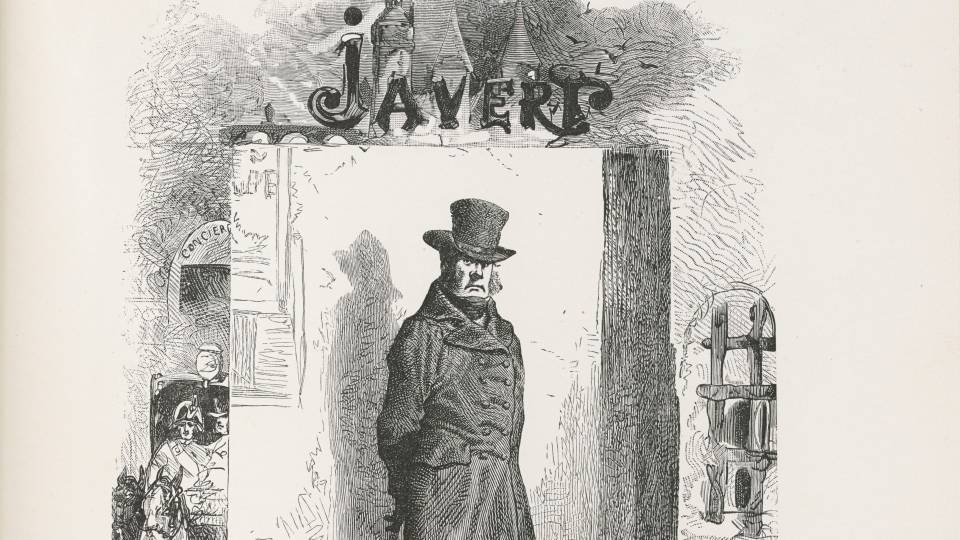

Illustration by Gustave Brion, 1862. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

SPOILER ALERT: This blog post discusses important plot points in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables.

I recently finished reading that consummate Christian classic: Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. It is a massive tome and covers a lot of ground both in terms of plot and in terms of thought. But one moment toward the end of the story really struck me, and I want to reflect on it here: the death of Inspector Javert.

I realize that many people will not have read the novel, but it seems to me that, especially with the immense popularity of the musical adaptation, which is now even more accessible through the recent film version (2012) starring Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe, the basic plot and major characters of Les Misérables are a part of our mainstream cultural awareness.

Here’s a brief summary with only the most relevant details for those who don’t know the story or do but need a little refresher:

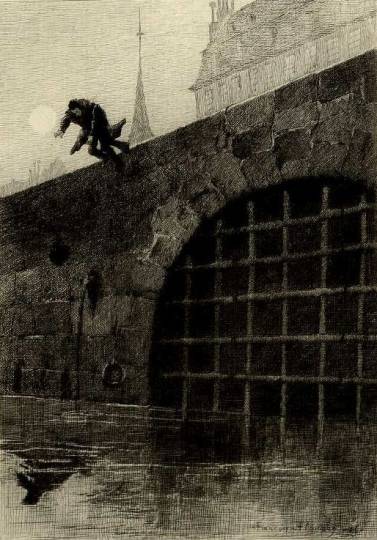

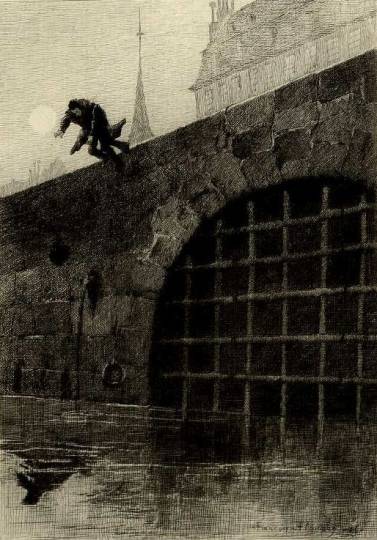

A man named Jean Valjean completes his terms of hard labour and imprisonment for theft. He encounters an act of mercy which sets him on a course of life in which he tries to do as much good as he can. But before this conversion is complete (and in fact it is this very act which completes his conversion), he commits another crime. Years later, he is discovered, and despite his new way of life, he is condemned again, this time for life. He escapes and is generally believed to have died. From time to time a police officer appears in the narrative: Inspector Javert. He knows Jean Valjean and more than once tries to bring him to justice, that is, to serve out his allotted sentence. Towards the end of the book, during an armed uprising on the streets of Paris, Javert is captured by the insurgents as a spy. Jean Valjean is given the task of executing the spy, but instead he lets him go. Later that same day, Javert has the opportunity to arrest Jean Valjean, the other man offering no resistance, but he lets him go. These last two events send Javert’s mind into great confusion, which he resolves by leaping from the parapet of a bridge into a dangerous part of the Seine and drowning himself.

Javert is a caricature of sorts but a very recognizable one. He is the man who is afraid of uncertainty, the man who cannot abide questions. He is the man we are all in danger of becoming: the one who barricades himself behind rules and regulations so that he might not be required to think or feel and so that he can always be right.

What struck me especially about Javert’s moment of perplexity was the role of God and conscience in it. Hugo brings Javert to a moment in which, for the first time in his life, he is faced with two choices and he does not know which to choose because he suddenly sees that both are good and both are bad. It is the awakening of his conscience, that is, God speaking within him. All of his life up to that point, his beliefs, and his convictions clearly indicate the rightness of arresting an escaped convict. Yet something within him identifies a higher right in returning mercy to one who has shown him mercy. Running blindly along the straight and narrow path, he has smashed into God, and it shatters him. His world falls apart. He cannot henceforth be the same person. Two options are left to him: to bend like Jean Valjean or like St. Paul and let himself be remade by God, or to destroy himself. And he has made himself so rigid with all his rules and regulations, with his worship of earthly authority, that he cannot bend to what he recognizes as a higher authority.

As Christians, and maybe especially as Catholics, we often have a distorted view of conscience or even what it means to have a well-formed conscience. How often do we look to the Bible or to the Catechism to find solutions to specific dilemmas in our lives? Or probably more often, to justify our actions or even to condemn others?

That’s not what the Bible or the Catechism are for. That’s not how it works. But we do it because it’s easier to appeal to an unassailable authority, even one opportunistically interpreted by ourselves, than to think and to feel and to take responsibility for our decisions. It’s easier to dip in and out of convenient texts than to immerse ourselves in the whole of Church teaching and to open ourselves up to the transformative power of God. Because that invites uncertainty.

But uncertainty, it seems, is what we are called to as Christians.

Often in our lives, we are faced with moments like Javert’s when we have to make a decision and the answer is not entirely clear: the “right” answer somehow seems wrong, and the “wrong” answer somehow seems right. What do you do?

Unfortunately, at this point it’s too late to go running to the Bible or the Catechism for an answer. This is a job for the conscience, and the conscience is formed over a lifetime of being steeped in Church teachings. And by Church teachings I mean all of them, including the ones which seem inconvenient or confusing or unclear – and not just the ones that detail how we ought to regulate our behaviour but also the ones that teach what we believe and especially the one about how our lives should be lived in loving relationship with God and with one another.

And that is the key. While knowledge of rules and regulations is good and helpful, the conscience requires more than the law. It requires first and foremost an intimate relationship with the Lawmaker: the God of mercy and compassion, the God who is love.

If our faith and our understanding of our faith are based on laws and rules and regulations, we become like Javert, who takes a good and turns it into evil. We become incomplete human beings who discard the Lawgiver in order to make an idol of law. Because law is safe. Law is clear. There is no uncertainty with law. But as Christians we are not called to certainty; we are called to abandonment. With certainty, there is no room for trust.

The purpose of our lives on this earth is to open ourselves up to God. When we become too obsessed with “doing the right thing” or with “being right,” then we’ve lost our way because the way of love is higher and that is the way that leads to God. If we obsess too much over what is right and if we concern ourselves too much with condemning those who do wrong, then we risk becoming like Javert: narrow-minded and hard-hearted to the extent that when at last we encounter God, there is no room for Him in our hearts, and we risk losing everything.

Illustration of Javert's suicide by François Flameng. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Related Articles:

<<