Titus Brandsma: Saint of Dachau

Kristina Glicksman

Monday, May 9, 2022

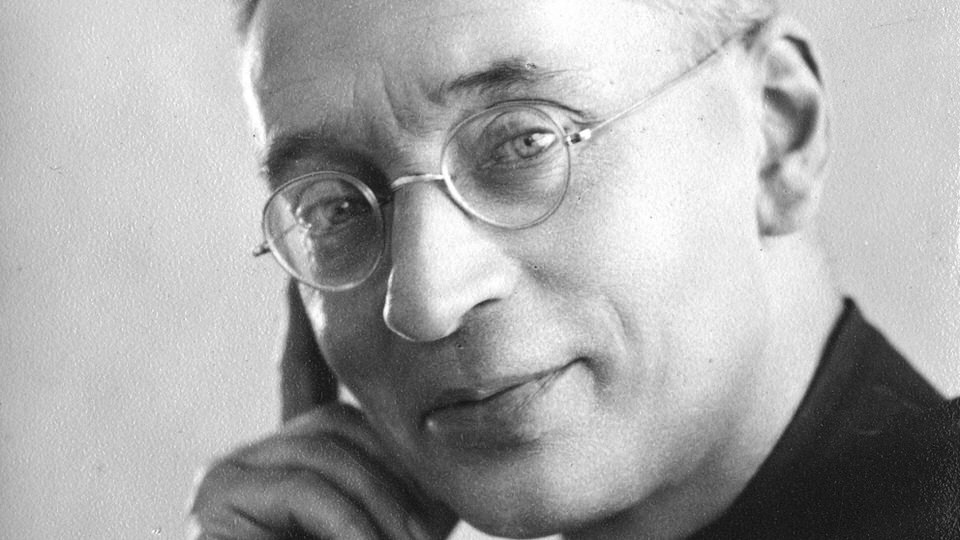

Titus Brandsma, age 42. Blessed Titus will be canonized on May 15, 2022. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

On May 15, Pope Francis will canonize Titus Brandsma, a Dutch Carmelite priest who was killed in the infamous Dachau concentration camp in 1942. Although the circumstances of his death made him a martyr, it is the holiness of his life and the courage and faithfulness with which he approached his imprisonment and death that make him a saint.

Early life

Born Anno Sjoerd Brandsma in 1881, he grew up in a devout Catholic family on a dairy farm in the Netherlands. At the age of 17, he entered the Carmelite monastery at Boxmeer and took the name Titus after his father. In 1905, he was ordained to the priesthood and was soon sent by his order to study in Rome, where he received a doctorate in philosophy.

University professor and student of mysticism

In 1923, Titus joined the faculty of the brand new Catholic University of Nijmegen (now Radboud University) as a professor of philosophy and the history of mysticism. Although he was certainly an intelligent and capable academic, he was best known for his personality: for his goodness, kindness, and cheerfulness and his openness to everyone.

But above all, he was a Carmelite friar with a great interest in his order’s tradition of mysticism (he was particularly attached to St. Teresa of Ávila), both in studying it and in trying to live it out. He had a profound understanding of the dignity of every human person and of the importance of having God at the centre of each person’s life. And those two aspects – understanding the nearness of God in all things and the dignity of each person – were the great foundation for his heroic martyrdom.

Arrest and imprisonment

In the 1930s, as national socialism gained force in Germany, it also tried to establish a foothold in the Netherlands, where it was vigorously opposed by all the Christian churches. When in 1940, the country fell to the invading German forces, the churches kept up their united front of vocal opposition to the evils of Nazism, denouncing in particular the persecution of Jews. (As a side note: this fight against Nazism actually provided an ecumenical rallying point for Dutch Christians, who had historically experienced deep divisions along confessional lines.)

As a professor and a priest, Blessed Titus added his voice to the chorus of Dutch Christian protest. But he also had another responsibility. In 1935, he had been appointed spiritual advisor to the body of Catholic journalists who made up the staff of more than 30 Catholic newspapers across the country. Now, early in 1942, he was asked to deliver by hand to the editors of each of these newspapers a letter from the bishops instructing them to disobey a new law which required them to print official Nazi propaganda.

At the age of 60 and fully aware of the risk he ran, the mild-mannered Carmelite professor managed to deliver 14 of his messages before being arrested on January 19. Five months later, he arrived in Dachau, where he died by a lethal injection of carbolic acid on July 26.

Final witness of prisoner 30492

The few letters Titus was able to send to his family and his superiors during his imprisonment bear witness to a gentle, joyful soul who approached life with a spirit of holy indifference and even viewed his particular circumstance with humour. Far from complaining about his initial solitary confinement, he welcomed it as an opportunity for the silence his Carmelite spirit craved.

Later, when he was moved to a different prison, though inwardly he may have regretted the loss of his solitude, outwardly, he became a source of hope and consolation to the men with whom he shared this time of trial. Even in Dachau, where he was beaten and subjected to hard labour despite his age and frail health, his gentleness and cheerfulness never left him. While others supported him physically – carrying him back to camp after the day’s labour – he lifted them up spiritually, encouraging them by word and example to do the seemingly impossible: to love and forgive those who treated them so mercilessly.

Even in his last days in the “hospital” (a site more for medical experimentation and torture than for healing), the nurse who delivered his final, fatal injection later testified that he was a source of strength to the others who were confined with him in that terrible place and the inspiration for her own conversion.

Miracle

In 2004, Carmelite priest Fr. Michael Driscoll was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer. He had learned about Fr. Brandsma growing up and had even attended his beatification ceremony in the Vatican in 1985. Before his surgery, he prayed frequently with a relic of Blessed Titus (a small piece of his clothing), and friends began a prayer campaign asking for the fellow Carmelite’s intercession. Nearly two decades later, Fr. Driscoll is not only still alive but still cancer-free – something which is scientifically inexplicable, according to doctors, given the severity of his case.

Possible patronage

Titus Brandsma would be a great patron for Catholic journalists – whether they work in Catholic or secular media. At a time when freedom of the press was under great threat, he risked his life to bring spiritual and moral support to Catholic journalists so they could continue to stand for the truth. And it was for this that he died.

Today, the threat is different and the risks are not the same, but journalists in the West who profess a Christian faith must increasingly find themselves at odds with the dominant secular culture, which has little patience for those who think differently. Now as then, St. Titus Brandsma can be a source of encouragement and consolation.

“I am already quite at home in this small cell. I have not yet got bored here, just the contrary. I am alone, certainly, but never was Our Lord so near to me. I could shout for joy because he made me find him again entirely, without me being able to go to see people, nor people me. Now he is my only refuge, and I feel secure and happy. I would stay here for ever, if he so disposed. Seldom have I been so happy and content.” – from “My Cell”, written in Scheveningen prison, January 27, 1942

Prayer for the Canonization of Titus Brandsma

God of peace and justice,

you open our hearts to love

and to the joy of the Gospel

even in the midst of countless forms of violence

that take away the dignity of our brothers and sisters,

fill us with your grace,

so that like Saint Titus Brandsma,

we may in tenderness see beyond the horrors of inhumanity

and contemplate your glory

that shines forth through the martyrs of every age,

and so become your authentic witnesses in the world of today.

Amen.

Related Articles:

<<