The Gospel, reenchanted: An interview with Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick

Salt + Light Media

Tuesday, March 8, 2022

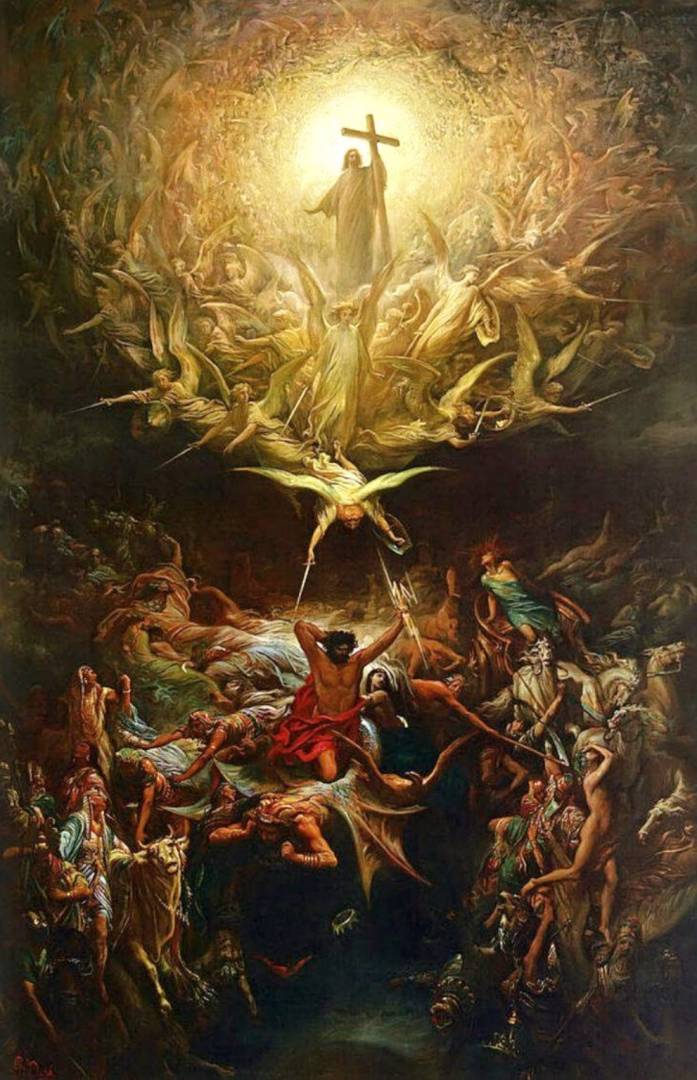

Detail of The Triumph of Christianity Over Paganism (upper half) by Gustave Doré (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick is an Orthodox Christian priest and the Chief Content Officer at Ancient Faith Ministries. Author of many books and host of various podcasts, he recently spoke with Benjamin Boivin about his latest book, Arise, O God: The Gospel of Christ's Defeat of Demons, Sin, and Death. (You can read a review of the book here.) This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Boivin: Your latest book, Arise, O God, is a short but profound account of the Gospel. But, of course, after 2000 years of Christianity, one might be tempted to ask if there is any need for yet another book about the Gospel. What were your motivations in writing this?

Damick: It's a good question. I have to admit I had to overcome a bit of trepidation when I thought about writing it because it seems like an act of hubris, really, to write a book about the Gospel. But the reason why I decided to write what I did is that the Gospel has to be expressed in every generation in a way that is understandable to that generation. Now, if we are being faithful to it we don't change the actual content of it, but we do need to change the way it is expressed so that it can be understandable, especially because the first people who heard it had a very different context, very different cultural understanding, a different language, a different political world, a different religious world than we do in our time.

So the reason that I wrote it is that I couldn't find a book that did the job the way that I wanted it to in my own teaching. I use other people's books when I'm teaching things, but I couldn't find what I wanted in this particular case. The purpose is really to try to express in a fresh way what is always being expressed by the Christian Church.

You start off by asking a question many people never really seem to wonder about: “What is a gospel?” You talk about the gospel as a literary genre, and in fact a pre-Christian one. Can you tell us more about that?

Right. So that's one of the big differences between the first century and our time. In our time the word “gospel”, at least in English, is basically a religious word. People think of it as the good news about Jesus Christ. And often people look at the original Greek word evangelion, and they translate it literally: “good” “news”. That's what the parts of the word mean, but the word evangelion in Greek did not simply mean news that is good, in the first century.

I think that that's important because if we're going to receive the message itself that is the Gospel, then we need to understand why it was called a gospel. If I hand you a novel and I say, “This is a novel”, you're going to receive that story in a different way than if I said, “This is someone's life story”. It could literally be the exact same content, but if you have a very different frame for receiving then you're going to understand what's in it in a different way.

And so this question of what is the genre “gospel” is a really important one. When it was used in the first century in the Greco-Roman world, a gospel was the announcement of a victory, a military victory. The way it would work is that a herald would come into your town or your city, and he would get down off his horse and he would proclaim the gospel – usually in the plural, evangelia, the gospels – that he had been given to proclaim.

That would include three things. He would tell who the identity of his master was, often including a big list of titles. Also, he would tell what he had accomplished, which was usually the victory he had won out in the fields near your city, which meant that he was now the overlord, coming to town. But maybe a big list of victories as well. And the third thing was always what he expected of the people he was going to rule.

That's what the genre of gospel was in the first century, and so when the writers of the Gospel picked that word to describe what the texts they're writing are, then that is how people received it. That's the announcement of a victory – which is not the way most people in the 21st century English-speaking world understand what that means at all. The envelope in which we receive the message is very different than it was in the very first century.

How should we understand the Gospel – that is to say, the Gospel of Jesus Christ – in light of what you just said? Why is it that we even have a Gospel in the first place?

It's the report of a victory, the announcement of a victory, primarily. And so the question one would ask is: victory by whom over whom? Certainly, this would not be too far outside the way most modern people understand the Gospel. They might be surprised to hear that it's the report of a victory, but then they think: “Oh well, it's the victory over sin”, which – I mean it's true, right? – or the victory over death – also true. But it had a much more visceral and immediate meaning in the first century, which is that it was the victory over demons.

The ancient world understood that the world was filled with spiritual presences, some good, some bad. All Christians believe in angels, or they should anyway, and all Christians believe in demons, but we tend to kind of push them off to the margins of what it means to be Christian and to not have a sense of them being really super actively involved all the time. Ancient people had a strong sense that spirits were always involved in their lives, and so early Christianity set itself up in opposition to paganism because paganism was understood to be a slavery that demons were exercising over their worshippers.

When Christ's victory is reported, through the Gospel, as His Gospel, what is being said is: “He has defeated the demons that you have been worshipping, and He has liberated you from them. Now He's in charge.” Now, if you understand the whole arc of Scripture, you understand that what is happening is actually a reconquest. This was Christ's world to begin with. He made it, and then it was assigned to angelic powers to govern by proxy, and then those fell by accepting worship from people, and that's the origin of paganism.

That slavery to demons gets deeper and deeper and deeper; it gets worse and worse and worse. The idea that demons were this dominating, enslaving force would have been very, very clear in the ancient world. It's not like people only had this tendency toward sin, the way that we experience it now, although certainly they had that. The world itself was vile. It was way beyond unfair. It was brutal, dominating, and just awful for almost everybody, except for those who were at the top.

It's just a fight for survival for a lot of people, and those who were at the top dominated those at the bottom, and that's the way the whole religion itself was set up, that's the way paganism works. You would not want to be in the ancient Roman empire. Only a handful of people were actually citizens of the Roman empire and enjoyed the privileges of citizenship, which were still nowhere near what the average citizen in almost any country in the world today enjoys.

The vast majority of people who lived in the Roman empire were actually defined as non personae, not even persons. It was especially bad for women, especially bad for children, peasants, and poor people. It was the worst. When the Gospel of Christ is preached, it is to say that this whole system which is controlled, influenced, dominated, and livened by demonic powers, that it is all being crushed and destroyed. Christ is coming to retake and to rescue what is His. That's why there is a Gospel at all, because of this slavery to demonic forces.

Boivin: Your latest book, Arise, O God, is a short but profound account of the Gospel. But, of course, after 2000 years of Christianity, one might be tempted to ask if there is any need for yet another book about the Gospel. What were your motivations in writing this?

Damick: It's a good question. I have to admit I had to overcome a bit of trepidation when I thought about writing it because it seems like an act of hubris, really, to write a book about the Gospel. But the reason why I decided to write what I did is that the Gospel has to be expressed in every generation in a way that is understandable to that generation. Now, if we are being faithful to it we don't change the actual content of it, but we do need to change the way it is expressed so that it can be understandable, especially because the first people who heard it had a very different context, very different cultural understanding, a different language, a different political world, a different religious world than we do in our time.

So the reason that I wrote it is that I couldn't find a book that did the job the way that I wanted it to in my own teaching. I use other people's books when I'm teaching things, but I couldn't find what I wanted in this particular case. The purpose is really to try to express in a fresh way what is always being expressed by the Christian Church.

You start off by asking a question many people never really seem to wonder about: “What is a gospel?” You talk about the gospel as a literary genre, and in fact a pre-Christian one. Can you tell us more about that?

Right. So that's one of the big differences between the first century and our time. In our time the word “gospel”, at least in English, is basically a religious word. People think of it as the good news about Jesus Christ. And often people look at the original Greek word evangelion, and they translate it literally: “good” “news”. That's what the parts of the word mean, but the word evangelion in Greek did not simply mean news that is good, in the first century.

I think that that's important because if we're going to receive the message itself that is the Gospel, then we need to understand why it was called a gospel. If I hand you a novel and I say, “This is a novel”, you're going to receive that story in a different way than if I said, “This is someone's life story”. It could literally be the exact same content, but if you have a very different frame for receiving then you're going to understand what's in it in a different way.

And so this question of what is the genre “gospel” is a really important one. When it was used in the first century in the Greco-Roman world, a gospel was the announcement of a victory, a military victory. The way it would work is that a herald would come into your town or your city, and he would get down off his horse and he would proclaim the gospel – usually in the plural, evangelia, the gospels – that he had been given to proclaim.

That would include three things. He would tell who the identity of his master was, often including a big list of titles. Also, he would tell what he had accomplished, which was usually the victory he had won out in the fields near your city, which meant that he was now the overlord, coming to town. But maybe a big list of victories as well. And the third thing was always what he expected of the people he was going to rule.

That's what the genre of gospel was in the first century, and so when the writers of the Gospel picked that word to describe what the texts they're writing are, then that is how people received it. That's the announcement of a victory – which is not the way most people in the 21st century English-speaking world understand what that means at all. The envelope in which we receive the message is very different than it was in the very first century.

How should we understand the Gospel – that is to say, the Gospel of Jesus Christ – in light of what you just said? Why is it that we even have a Gospel in the first place?

It's the report of a victory, the announcement of a victory, primarily. And so the question one would ask is: victory by whom over whom? Certainly, this would not be too far outside the way most modern people understand the Gospel. They might be surprised to hear that it's the report of a victory, but then they think: “Oh well, it's the victory over sin”, which – I mean it's true, right? – or the victory over death – also true. But it had a much more visceral and immediate meaning in the first century, which is that it was the victory over demons.

The ancient world understood that the world was filled with spiritual presences, some good, some bad. All Christians believe in angels, or they should anyway, and all Christians believe in demons, but we tend to kind of push them off to the margins of what it means to be Christian and to not have a sense of them being really super actively involved all the time. Ancient people had a strong sense that spirits were always involved in their lives, and so early Christianity set itself up in opposition to paganism because paganism was understood to be a slavery that demons were exercising over their worshippers.

When Christ's victory is reported, through the Gospel, as His Gospel, what is being said is: “He has defeated the demons that you have been worshipping, and He has liberated you from them. Now He's in charge.” Now, if you understand the whole arc of Scripture, you understand that what is happening is actually a reconquest. This was Christ's world to begin with. He made it, and then it was assigned to angelic powers to govern by proxy, and then those fell by accepting worship from people, and that's the origin of paganism.

That slavery to demons gets deeper and deeper and deeper; it gets worse and worse and worse. The idea that demons were this dominating, enslaving force would have been very, very clear in the ancient world. It's not like people only had this tendency toward sin, the way that we experience it now, although certainly they had that. The world itself was vile. It was way beyond unfair. It was brutal, dominating, and just awful for almost everybody, except for those who were at the top.

It's just a fight for survival for a lot of people, and those who were at the top dominated those at the bottom, and that's the way the whole religion itself was set up, that's the way paganism works. You would not want to be in the ancient Roman empire. Only a handful of people were actually citizens of the Roman empire and enjoyed the privileges of citizenship, which were still nowhere near what the average citizen in almost any country in the world today enjoys.

The vast majority of people who lived in the Roman empire were actually defined as non personae, not even persons. It was especially bad for women, especially bad for children, peasants, and poor people. It was the worst. When the Gospel of Christ is preached, it is to say that this whole system which is controlled, influenced, dominated, and livened by demonic powers, that it is all being crushed and destroyed. Christ is coming to retake and to rescue what is His. That's why there is a Gospel at all, because of this slavery to demonic forces.

Even as Christians, we sometimes have a limited understanding of who Jesus Christ really is and what the Gospel is revealing about him: his profound identity, the scope of his accomplishments, etc. Why do you think that is the case?

There are multiple reasons for this. One of the reasons is that when you push angels and demons off to the side, which happened in the Enlightenment and the onset of materialism and individualism that occurs beginning several centuries ago, then that means most of the world itself is a sort of flat, neutral space. And then Christians posit that there are these supernatural exceptions – “Here's God! Here's a miracle!” and that kind of thing, right? – rather than these things simply being part of the whole fabric of the way that the universe itself works, where everything is infused with spiritual presence.

There is a whole set of titles used for God in the Scriptures that actually make no sense if you don't have this understanding of other spirits, other divine spiritual beings that exist. He is called “God of gods”, “Lord of lords”, “King of kings”. People think that means He's above all earthly rulers, but that's actually not the way it's used in the Bible. I mean, that is a word the Bible uses: He's the “God of gods”. He's also called the “Most High God”, which is a comparative term; that means that there are lesser gods.

In the first chapter of John, Jesus is introduced. John talks about the Word of God whom we've known all this time. The One who is the Son of the Most High God, whom we've always known as being the one who presides over this whole divine council. He who became flesh and dwelt among us who have seen His glory, the glory of the unique Son of the Father.

The Jesus that most Christians envision these days is a much lesser Jesus. The emphasis is on the fact that He is flesh. Ok, yes, but He is also at the same time the Most High God, the Son of the Most High God; He's the King of kings, the Lord of lords, the Lord of hosts.

Another thing I would say that feeds into this problem is the great neglect of the Old Testament by many, many Christians. And the misunderstanding of it, even if they don't neglect it. As a result, all of these things that are said about who God is are brushed past as we read the Scriptures. I think that that's part of what's going on there.

I first came into contact with the work you do at Ancient Faith through Amon Sûl, a podcast about the Tolkien Legendarium in light of the Orthodox Christian faith. Then I came across this other podcast you have been co-hosting with Fr. Stephen De Young about the unseen world, called The Lord of Spirits. Of course, many of your listeners have noticed overlapping themes in the content you have been creating for a while, chiefly a notion of reenchantment. Is it fair to say that Arise, O God brings about a reenchanted understanding of the Gospel in such a noticeably disenchanted world?

I hope so! The question of reenchantment gets a lot of discussion, and it seems to be a growing conversation, I've noticed, although I didn't write Arise, O God in an attempt to join that conversation.

Let's use this word, reenchantment, to mean engaging with the world as it is in its fullness in both the seen and unseen elements. The reason why I put it that way, rather than just saying “seeing the world” for what it really is, is because I think that it's not just a question of seeing the world differently. It's not just a question of acknowledging or maybe perceiving that there is a reality that normally I don't see with my physical eyes or even my reasoning brain.

And it's not just about recognizing something or agreeing with something, a certain kind of knowledge that I know in my head. It's about the proper way to engage with the whole world as it truly, truly is. And I think that when we understand the right way to engage, the actual behaviours that we need to undertake, then this question of perception actually follows that.

I like the word enchantment, although some people don't like to talk about this because they think of magic spells and stuff. I'm not talking about magic spells. What I'm talking about is a way of engaging with the world in a way that is truly obedient and faithful to the full vision that the Scriptures give us and that the Church has preserved and explicated. What that means, for instance, is a way of prayer, a way of worship, a way of building churches... That's a great example. You can tell churches that are built with an enchanted theology, so to speak, that sees the whole world as infused with spiritual presence versus ones that are not. You immediately see it with your physical eyes.

You can also see this in the way that we live in our homes. In the Orthodox Church for instance, every single year, we have a priest come to our house and bless the house. Why do we do that? It's because we understand that the house has been spiritually defiled by our sins. And so the priest coming to bless the home annually is a way of purification so that the place is cleaned out so that we give ourselves the best possible environment in which to live holiness.

Coming from a Roman Catholic perspective, I found what you've been doing – whether it be the enchantment metanarrative or a lot of what you say about the Gospel – truly relevant for Catholics and often reflected in the Catholic tradition as well. From your perspective, what is it in the Orthodox tradition that makes it especially capable of bringing about reenchantment?

I think that the Orthodox tradition has preserved and expressed this engagement with the world as it truly is in the richest possible way, frankly, as compared to all other Christian traditions that now exist. I'm not Catholic, so I can't speak for the Roman Catholic Church, but I can at least observe that in recent history, a lot of that has been laid aside. You can see it architecturally, you can see it liturgically, you can see it in lots of ways. Asceticism is radically reduced, all of these things.

And then certainly within much of Protestantism – of course, I'm speaking very broadly – there is the idea of four bare walls and a sermon, which then gets reacted against, especially in the charismatic influenced world, by spectacle. So you fill up the space now with lights and fog machines and loud music and this kind of stuff, with theatre, with concerts. The thing is that that doesn't enchant either. It doesn't do that. In fact, it's profoundly materialistic.

I used to work as a stagehand before I went to the seminary, and one of the moments I have had as I was on my way out of Protestantism was the realization that my professional life, which included theatrical productions, including concerts and stuff – that that was much higher quality than the lesser version of that I was getting on Sunday morning as an evangelical.

So I think that the Orthodox tradition, that this is what it has to offer to a world that's been disenchanted. We never cast that aside. Now, that's not to say Orthodox Christians all engage with it in the fullest possible way, but we never locked that away anywhere and said, “That's not what we're doing anymore.”

Even if all people have is this sort of aesthetic sense that this is what we do, they're still being exposed to this full-bodied, fully enchanted experience of the Christian life just by showing up to church on Sunday. Even if they don't do any of the rest. But if all they do is just show up to church on Sunday, something is going to be happening there. Not just a kind of experience but actually something that's happening to them.

It does something to you. It's not just something you see or learn or experience; it does something to you. When the deacon or the priest comes out with a censer, that is, to purify the space and the people in it, to prepare them to commune, it's not smells and bells, kind of like: “Well, that's nice”, or an ornamentation that makes it nicer. It actually has an effect; it actually does do something. That to me is one of the biggest questions people should ask about worship services. Not just what does it mean, or how does it work, but what does this do? What is it doing to the people who are there?

In addition to everything I just said about worship, which would be the biggest thing I have to say about this, also there is a very strong tradition of asceticism. Certainly, asceticism exists within the Roman Catholic tradition, but it is generally very muted when it comes to individual people in the Church.

And it's not just specific practices, but it's a whole kind of ethos of what it means to be Christian. The Divine Liturgy itself is ascetical, not just because one comes having fasted, undergone prayer, and so forth. Asceticism, at its heart, is actually turning away from one's personal desires and becoming refocused on Christ. It's hard to do that if you're not doing things like fasting because what happens is every single day, every single hour of the day, you're teaching yourself that your desires are what comes first. And then you're supposed to, for two hours on Sunday, put your desires somewhere else. People do that, but you've been training yourself not to. So it's really hard to do it well when your training is going in all different directions.

Fasting is so much more needed now. Especially in American culture, where everything you could possibly want is within moments of you being able to have it, especially in terms of food. The only thing that limits you might be how much money you have. But even then, you don't have to be very wealthy. You can eat better than almost everybody in history, anywhere. The idea that you could press a couple of buttons and a meat sandwich appears on your doorstep, that is the kind of thing that only kings could dream about in most of history. And so I think fasting is even more needed now because so much about our society is training us to be very self-focused.

These are things that I think the Orthodox Church practises. I won't say it's unique to us but it does tend to be concentrated in the Orthdox Church in a way that you don't see in most other places. There are certainly some big and good exceptions, but I think that's generally true.

Even as Christians, we sometimes have a limited understanding of who Jesus Christ really is and what the Gospel is revealing about him: his profound identity, the scope of his accomplishments, etc. Why do you think that is the case?

There are multiple reasons for this. One of the reasons is that when you push angels and demons off to the side, which happened in the Enlightenment and the onset of materialism and individualism that occurs beginning several centuries ago, then that means most of the world itself is a sort of flat, neutral space. And then Christians posit that there are these supernatural exceptions – “Here's God! Here's a miracle!” and that kind of thing, right? – rather than these things simply being part of the whole fabric of the way that the universe itself works, where everything is infused with spiritual presence.

There is a whole set of titles used for God in the Scriptures that actually make no sense if you don't have this understanding of other spirits, other divine spiritual beings that exist. He is called “God of gods”, “Lord of lords”, “King of kings”. People think that means He's above all earthly rulers, but that's actually not the way it's used in the Bible. I mean, that is a word the Bible uses: He's the “God of gods”. He's also called the “Most High God”, which is a comparative term; that means that there are lesser gods.

In the first chapter of John, Jesus is introduced. John talks about the Word of God whom we've known all this time. The One who is the Son of the Most High God, whom we've always known as being the one who presides over this whole divine council. He who became flesh and dwelt among us who have seen His glory, the glory of the unique Son of the Father.

The Jesus that most Christians envision these days is a much lesser Jesus. The emphasis is on the fact that He is flesh. Ok, yes, but He is also at the same time the Most High God, the Son of the Most High God; He's the King of kings, the Lord of lords, the Lord of hosts.

Another thing I would say that feeds into this problem is the great neglect of the Old Testament by many, many Christians. And the misunderstanding of it, even if they don't neglect it. As a result, all of these things that are said about who God is are brushed past as we read the Scriptures. I think that that's part of what's going on there.

I first came into contact with the work you do at Ancient Faith through Amon Sûl, a podcast about the Tolkien Legendarium in light of the Orthodox Christian faith. Then I came across this other podcast you have been co-hosting with Fr. Stephen De Young about the unseen world, called The Lord of Spirits. Of course, many of your listeners have noticed overlapping themes in the content you have been creating for a while, chiefly a notion of reenchantment. Is it fair to say that Arise, O God brings about a reenchanted understanding of the Gospel in such a noticeably disenchanted world?

I hope so! The question of reenchantment gets a lot of discussion, and it seems to be a growing conversation, I've noticed, although I didn't write Arise, O God in an attempt to join that conversation.

Let's use this word, reenchantment, to mean engaging with the world as it is in its fullness in both the seen and unseen elements. The reason why I put it that way, rather than just saying “seeing the world” for what it really is, is because I think that it's not just a question of seeing the world differently. It's not just a question of acknowledging or maybe perceiving that there is a reality that normally I don't see with my physical eyes or even my reasoning brain.

And it's not just about recognizing something or agreeing with something, a certain kind of knowledge that I know in my head. It's about the proper way to engage with the whole world as it truly, truly is. And I think that when we understand the right way to engage, the actual behaviours that we need to undertake, then this question of perception actually follows that.

I like the word enchantment, although some people don't like to talk about this because they think of magic spells and stuff. I'm not talking about magic spells. What I'm talking about is a way of engaging with the world in a way that is truly obedient and faithful to the full vision that the Scriptures give us and that the Church has preserved and explicated. What that means, for instance, is a way of prayer, a way of worship, a way of building churches... That's a great example. You can tell churches that are built with an enchanted theology, so to speak, that sees the whole world as infused with spiritual presence versus ones that are not. You immediately see it with your physical eyes.

You can also see this in the way that we live in our homes. In the Orthodox Church for instance, every single year, we have a priest come to our house and bless the house. Why do we do that? It's because we understand that the house has been spiritually defiled by our sins. And so the priest coming to bless the home annually is a way of purification so that the place is cleaned out so that we give ourselves the best possible environment in which to live holiness.

Coming from a Roman Catholic perspective, I found what you've been doing – whether it be the enchantment metanarrative or a lot of what you say about the Gospel – truly relevant for Catholics and often reflected in the Catholic tradition as well. From your perspective, what is it in the Orthodox tradition that makes it especially capable of bringing about reenchantment?

I think that the Orthodox tradition has preserved and expressed this engagement with the world as it truly is in the richest possible way, frankly, as compared to all other Christian traditions that now exist. I'm not Catholic, so I can't speak for the Roman Catholic Church, but I can at least observe that in recent history, a lot of that has been laid aside. You can see it architecturally, you can see it liturgically, you can see it in lots of ways. Asceticism is radically reduced, all of these things.

And then certainly within much of Protestantism – of course, I'm speaking very broadly – there is the idea of four bare walls and a sermon, which then gets reacted against, especially in the charismatic influenced world, by spectacle. So you fill up the space now with lights and fog machines and loud music and this kind of stuff, with theatre, with concerts. The thing is that that doesn't enchant either. It doesn't do that. In fact, it's profoundly materialistic.

I used to work as a stagehand before I went to the seminary, and one of the moments I have had as I was on my way out of Protestantism was the realization that my professional life, which included theatrical productions, including concerts and stuff – that that was much higher quality than the lesser version of that I was getting on Sunday morning as an evangelical.

So I think that the Orthodox tradition, that this is what it has to offer to a world that's been disenchanted. We never cast that aside. Now, that's not to say Orthodox Christians all engage with it in the fullest possible way, but we never locked that away anywhere and said, “That's not what we're doing anymore.”

Even if all people have is this sort of aesthetic sense that this is what we do, they're still being exposed to this full-bodied, fully enchanted experience of the Christian life just by showing up to church on Sunday. Even if they don't do any of the rest. But if all they do is just show up to church on Sunday, something is going to be happening there. Not just a kind of experience but actually something that's happening to them.

It does something to you. It's not just something you see or learn or experience; it does something to you. When the deacon or the priest comes out with a censer, that is, to purify the space and the people in it, to prepare them to commune, it's not smells and bells, kind of like: “Well, that's nice”, or an ornamentation that makes it nicer. It actually has an effect; it actually does do something. That to me is one of the biggest questions people should ask about worship services. Not just what does it mean, or how does it work, but what does this do? What is it doing to the people who are there?

In addition to everything I just said about worship, which would be the biggest thing I have to say about this, also there is a very strong tradition of asceticism. Certainly, asceticism exists within the Roman Catholic tradition, but it is generally very muted when it comes to individual people in the Church.

And it's not just specific practices, but it's a whole kind of ethos of what it means to be Christian. The Divine Liturgy itself is ascetical, not just because one comes having fasted, undergone prayer, and so forth. Asceticism, at its heart, is actually turning away from one's personal desires and becoming refocused on Christ. It's hard to do that if you're not doing things like fasting because what happens is every single day, every single hour of the day, you're teaching yourself that your desires are what comes first. And then you're supposed to, for two hours on Sunday, put your desires somewhere else. People do that, but you've been training yourself not to. So it's really hard to do it well when your training is going in all different directions.

Fasting is so much more needed now. Especially in American culture, where everything you could possibly want is within moments of you being able to have it, especially in terms of food. The only thing that limits you might be how much money you have. But even then, you don't have to be very wealthy. You can eat better than almost everybody in history, anywhere. The idea that you could press a couple of buttons and a meat sandwich appears on your doorstep, that is the kind of thing that only kings could dream about in most of history. And so I think fasting is even more needed now because so much about our society is training us to be very self-focused.

These are things that I think the Orthodox Church practises. I won't say it's unique to us but it does tend to be concentrated in the Orthdox Church in a way that you don't see in most other places. There are certainly some big and good exceptions, but I think that's generally true.

Boivin: Your latest book, Arise, O God, is a short but profound account of the Gospel. But, of course, after 2000 years of Christianity, one might be tempted to ask if there is any need for yet another book about the Gospel. What were your motivations in writing this?

Damick: It's a good question. I have to admit I had to overcome a bit of trepidation when I thought about writing it because it seems like an act of hubris, really, to write a book about the Gospel. But the reason why I decided to write what I did is that the Gospel has to be expressed in every generation in a way that is understandable to that generation. Now, if we are being faithful to it we don't change the actual content of it, but we do need to change the way it is expressed so that it can be understandable, especially because the first people who heard it had a very different context, very different cultural understanding, a different language, a different political world, a different religious world than we do in our time.

So the reason that I wrote it is that I couldn't find a book that did the job the way that I wanted it to in my own teaching. I use other people's books when I'm teaching things, but I couldn't find what I wanted in this particular case. The purpose is really to try to express in a fresh way what is always being expressed by the Christian Church.

You start off by asking a question many people never really seem to wonder about: “What is a gospel?” You talk about the gospel as a literary genre, and in fact a pre-Christian one. Can you tell us more about that?

Right. So that's one of the big differences between the first century and our time. In our time the word “gospel”, at least in English, is basically a religious word. People think of it as the good news about Jesus Christ. And often people look at the original Greek word evangelion, and they translate it literally: “good” “news”. That's what the parts of the word mean, but the word evangelion in Greek did not simply mean news that is good, in the first century.

I think that that's important because if we're going to receive the message itself that is the Gospel, then we need to understand why it was called a gospel. If I hand you a novel and I say, “This is a novel”, you're going to receive that story in a different way than if I said, “This is someone's life story”. It could literally be the exact same content, but if you have a very different frame for receiving then you're going to understand what's in it in a different way.

And so this question of what is the genre “gospel” is a really important one. When it was used in the first century in the Greco-Roman world, a gospel was the announcement of a victory, a military victory. The way it would work is that a herald would come into your town or your city, and he would get down off his horse and he would proclaim the gospel – usually in the plural, evangelia, the gospels – that he had been given to proclaim.

That would include three things. He would tell who the identity of his master was, often including a big list of titles. Also, he would tell what he had accomplished, which was usually the victory he had won out in the fields near your city, which meant that he was now the overlord, coming to town. But maybe a big list of victories as well. And the third thing was always what he expected of the people he was going to rule.

That's what the genre of gospel was in the first century, and so when the writers of the Gospel picked that word to describe what the texts they're writing are, then that is how people received it. That's the announcement of a victory – which is not the way most people in the 21st century English-speaking world understand what that means at all. The envelope in which we receive the message is very different than it was in the very first century.

How should we understand the Gospel – that is to say, the Gospel of Jesus Christ – in light of what you just said? Why is it that we even have a Gospel in the first place?

It's the report of a victory, the announcement of a victory, primarily. And so the question one would ask is: victory by whom over whom? Certainly, this would not be too far outside the way most modern people understand the Gospel. They might be surprised to hear that it's the report of a victory, but then they think: “Oh well, it's the victory over sin”, which – I mean it's true, right? – or the victory over death – also true. But it had a much more visceral and immediate meaning in the first century, which is that it was the victory over demons.

The ancient world understood that the world was filled with spiritual presences, some good, some bad. All Christians believe in angels, or they should anyway, and all Christians believe in demons, but we tend to kind of push them off to the margins of what it means to be Christian and to not have a sense of them being really super actively involved all the time. Ancient people had a strong sense that spirits were always involved in their lives, and so early Christianity set itself up in opposition to paganism because paganism was understood to be a slavery that demons were exercising over their worshippers.

When Christ's victory is reported, through the Gospel, as His Gospel, what is being said is: “He has defeated the demons that you have been worshipping, and He has liberated you from them. Now He's in charge.” Now, if you understand the whole arc of Scripture, you understand that what is happening is actually a reconquest. This was Christ's world to begin with. He made it, and then it was assigned to angelic powers to govern by proxy, and then those fell by accepting worship from people, and that's the origin of paganism.

That slavery to demons gets deeper and deeper and deeper; it gets worse and worse and worse. The idea that demons were this dominating, enslaving force would have been very, very clear in the ancient world. It's not like people only had this tendency toward sin, the way that we experience it now, although certainly they had that. The world itself was vile. It was way beyond unfair. It was brutal, dominating, and just awful for almost everybody, except for those who were at the top.

It's just a fight for survival for a lot of people, and those who were at the top dominated those at the bottom, and that's the way the whole religion itself was set up, that's the way paganism works. You would not want to be in the ancient Roman empire. Only a handful of people were actually citizens of the Roman empire and enjoyed the privileges of citizenship, which were still nowhere near what the average citizen in almost any country in the world today enjoys.

The vast majority of people who lived in the Roman empire were actually defined as non personae, not even persons. It was especially bad for women, especially bad for children, peasants, and poor people. It was the worst. When the Gospel of Christ is preached, it is to say that this whole system which is controlled, influenced, dominated, and livened by demonic powers, that it is all being crushed and destroyed. Christ is coming to retake and to rescue what is His. That's why there is a Gospel at all, because of this slavery to demonic forces.

Boivin: Your latest book, Arise, O God, is a short but profound account of the Gospel. But, of course, after 2000 years of Christianity, one might be tempted to ask if there is any need for yet another book about the Gospel. What were your motivations in writing this?

Damick: It's a good question. I have to admit I had to overcome a bit of trepidation when I thought about writing it because it seems like an act of hubris, really, to write a book about the Gospel. But the reason why I decided to write what I did is that the Gospel has to be expressed in every generation in a way that is understandable to that generation. Now, if we are being faithful to it we don't change the actual content of it, but we do need to change the way it is expressed so that it can be understandable, especially because the first people who heard it had a very different context, very different cultural understanding, a different language, a different political world, a different religious world than we do in our time.

So the reason that I wrote it is that I couldn't find a book that did the job the way that I wanted it to in my own teaching. I use other people's books when I'm teaching things, but I couldn't find what I wanted in this particular case. The purpose is really to try to express in a fresh way what is always being expressed by the Christian Church.

You start off by asking a question many people never really seem to wonder about: “What is a gospel?” You talk about the gospel as a literary genre, and in fact a pre-Christian one. Can you tell us more about that?

Right. So that's one of the big differences between the first century and our time. In our time the word “gospel”, at least in English, is basically a religious word. People think of it as the good news about Jesus Christ. And often people look at the original Greek word evangelion, and they translate it literally: “good” “news”. That's what the parts of the word mean, but the word evangelion in Greek did not simply mean news that is good, in the first century.

I think that that's important because if we're going to receive the message itself that is the Gospel, then we need to understand why it was called a gospel. If I hand you a novel and I say, “This is a novel”, you're going to receive that story in a different way than if I said, “This is someone's life story”. It could literally be the exact same content, but if you have a very different frame for receiving then you're going to understand what's in it in a different way.

And so this question of what is the genre “gospel” is a really important one. When it was used in the first century in the Greco-Roman world, a gospel was the announcement of a victory, a military victory. The way it would work is that a herald would come into your town or your city, and he would get down off his horse and he would proclaim the gospel – usually in the plural, evangelia, the gospels – that he had been given to proclaim.

That would include three things. He would tell who the identity of his master was, often including a big list of titles. Also, he would tell what he had accomplished, which was usually the victory he had won out in the fields near your city, which meant that he was now the overlord, coming to town. But maybe a big list of victories as well. And the third thing was always what he expected of the people he was going to rule.

That's what the genre of gospel was in the first century, and so when the writers of the Gospel picked that word to describe what the texts they're writing are, then that is how people received it. That's the announcement of a victory – which is not the way most people in the 21st century English-speaking world understand what that means at all. The envelope in which we receive the message is very different than it was in the very first century.

How should we understand the Gospel – that is to say, the Gospel of Jesus Christ – in light of what you just said? Why is it that we even have a Gospel in the first place?

It's the report of a victory, the announcement of a victory, primarily. And so the question one would ask is: victory by whom over whom? Certainly, this would not be too far outside the way most modern people understand the Gospel. They might be surprised to hear that it's the report of a victory, but then they think: “Oh well, it's the victory over sin”, which – I mean it's true, right? – or the victory over death – also true. But it had a much more visceral and immediate meaning in the first century, which is that it was the victory over demons.

The ancient world understood that the world was filled with spiritual presences, some good, some bad. All Christians believe in angels, or they should anyway, and all Christians believe in demons, but we tend to kind of push them off to the margins of what it means to be Christian and to not have a sense of them being really super actively involved all the time. Ancient people had a strong sense that spirits were always involved in their lives, and so early Christianity set itself up in opposition to paganism because paganism was understood to be a slavery that demons were exercising over their worshippers.

When Christ's victory is reported, through the Gospel, as His Gospel, what is being said is: “He has defeated the demons that you have been worshipping, and He has liberated you from them. Now He's in charge.” Now, if you understand the whole arc of Scripture, you understand that what is happening is actually a reconquest. This was Christ's world to begin with. He made it, and then it was assigned to angelic powers to govern by proxy, and then those fell by accepting worship from people, and that's the origin of paganism.

That slavery to demons gets deeper and deeper and deeper; it gets worse and worse and worse. The idea that demons were this dominating, enslaving force would have been very, very clear in the ancient world. It's not like people only had this tendency toward sin, the way that we experience it now, although certainly they had that. The world itself was vile. It was way beyond unfair. It was brutal, dominating, and just awful for almost everybody, except for those who were at the top.

It's just a fight for survival for a lot of people, and those who were at the top dominated those at the bottom, and that's the way the whole religion itself was set up, that's the way paganism works. You would not want to be in the ancient Roman empire. Only a handful of people were actually citizens of the Roman empire and enjoyed the privileges of citizenship, which were still nowhere near what the average citizen in almost any country in the world today enjoys.

The vast majority of people who lived in the Roman empire were actually defined as non personae, not even persons. It was especially bad for women, especially bad for children, peasants, and poor people. It was the worst. When the Gospel of Christ is preached, it is to say that this whole system which is controlled, influenced, dominated, and livened by demonic powers, that it is all being crushed and destroyed. Christ is coming to retake and to rescue what is His. That's why there is a Gospel at all, because of this slavery to demonic forces.

Detail of The Triumph of Christianity Over Paganism (lower half) by Gustave Doré (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

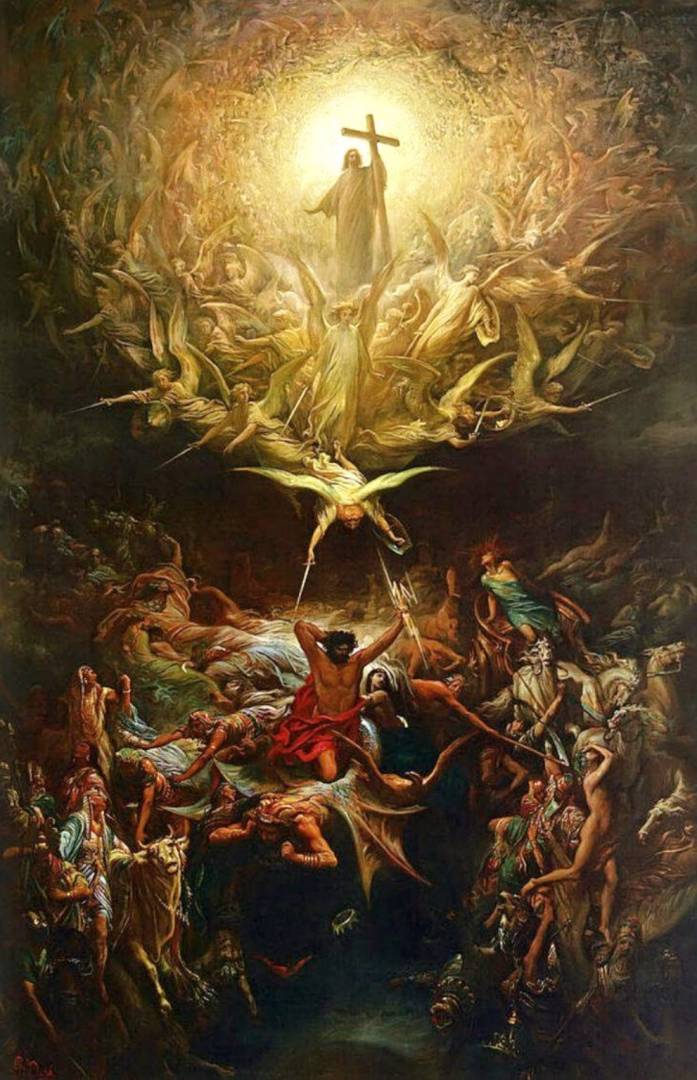

The Triumph of Christianity Over Paganism by Gustave Doré (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Related Articles:

<<