Telling them apart: Thomas Becket and Thomas More

Kristina Glicksman

Sunday, December 29, 2019

Detail of the "Becket casket" held by the V&A Museum in London. Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen (CC BY 2.5)

In our Catholic Christian tradition we’ve been blessed with many role models for holiness in our saints. But sometimes it can be difficult to keep them all straight. In this series, “Telling them apart,” I am presenting some side-by-side comparisons in order to help us keep track of commonly confused saints.Why is it that the memories of Mass which seem to stick most in our minds are not powerful spiritual insights or moving homilies or beautiful liturgical moments but the ones that are most human – the time your brother made you laugh out loud or the altar server dropped the book or the lady fainted during the Easter Vigil? One of my most enduring memories is of a homily preached at a weekday morning Mass on December 29th one year when I was home visiting my parents for Christmas. The celebrant chose to educate us about the saint whose feast we were commemorating that day: St. Thomas Becket. As he began the story, which was fairly familiar to me, I was surprised to hear details which I knew belonged to the life of St. Thomas More. Apparently, my mother recognized them as well because she shook her head through the entire homily, but unless he was telepathic, I’m not sure what the poor priest was supposed to do with that. It’s not just that he mistook one Thomas for the other, but he moved so fluidly between the 12th century and the 16th, the archbishop and the politician, that he created a kind of super saint with all the most memorable details from the lives of each. And as painful (in an empathetic way) as it was at the time and amusing in hindsight, it is really not at all surprising. They are two Thomases who were Chancellors of England and close friends of kings named Henry who had enormous egos and vile tempers. Both were embroiled in controversies which straddled the Church/state divide and put them in opposition to their former friends who ordered their deaths. Who wouldn’t get confused? The only solution to untangling these two Thomases is to get to know them a bit better.

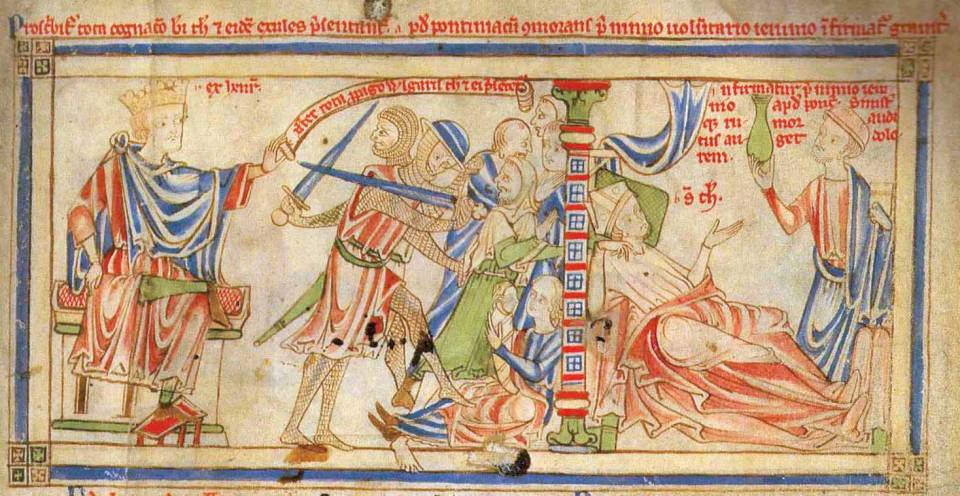

Initial C: The Martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket, about 1320 - 1325, Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment. Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program.

Thomas Becket (1118/1120 – 1170)

It is probably fair to say that Thomas Becket is the most famous and most popular English saint in history, though we in North America might be a little more familiar with Thomas More, partly because of our strange fascination with King Henry VIII and his many wives. Thomas Becket, or Thomas of London, as he was known in early life, was born to a Norman family (despite what we “learn” from the 1964 movie Becket), received a decent education, and became a clerk in the service of Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Thomas was not from a wealthy or influential family, but he must have been particularly good at his job (administration, mainly) because he rose quickly in the ranks, becoming a favourite of the archbishop. In 1154, he was ordained a deacon and appointed Archdeacon of Canterbury. This might not sound like much to us today, but that’s because the role of the deacon changed considerably after the Council of Trent in the 16th century. At the time we’re talking about, deacons had a lot more power and responsibility. And in England, the Archdeacon of Canterbury was the most powerful of them all because he was the righthand man of the Archbishop of Canterbury, who was the second most powerful man in England after the king. A few months after his ordination, “Thomas of London” became “Thomas the Chancellor”, when his archbishop offered him to the new, 21-year-old King of England, Henry II, for this very important administrative position. Despite the difference in age (about 13 years), Thomas and Henry became legendary friends, and Thomas became Henry’s most important and trusted adviser. And although he was a deacon, Thomas, as Chancellor, put the interests of his king before the interests of the Church when they came into conflict. And since this was a time in medieval Europe when legal precedents were being established and reformed and the Church was very much a politically and economically powerful entity, they frequently did. That’s probably not what Theobald was hoping for when he recommended Thomas to Henry for his Chancellor. But Henry made the same mistake. In 1161, Theobald died, and Henry insisted, over Thomas’ reservations, on appointing his best friend as the new Archbishop of Canterbury. (Kings had that power at that time – in practice if not in law.) So on June 2, 1162, Thomas was ordained a priest, and the next day, he was consecrated as bishop.

From The Becket Leaves (La vie de Seint Thomas de Cantorbéry), a French-verse history of the life of Thomas Becket with large illuminations. Left: Henry II banishes all Thomas Becket's people. Right: Becket lies sick at Pontigny Abbey, after excessive fasting. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket, about 1430 - 1440, Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment. Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program.

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages, And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes, To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes; And specially, from every shires ende Of Engelond, to Caunterbury they wende, The hooly blisful martir for to seke, That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

- from the Prologue to The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer

Thomas More (1478 – 1535)

Like his namesake, Thomas More was killed as much for political reasons as for religious ones, but unlike the archbishop, the case for his personal sanctity is much clearer. A man of great religious devotion even in his youth, he spent much time with the Carthusians in London and even contemplated becoming one. In the end, however, although he retained some of their devotional and penitential practices, he decided to become instead a lawyer and also a husband and father. More was reportedly a devoted family man and an affectionate father. He insisted on daily prayer as a family and also on educating his daughters to the same level as his son – much to the surprise and admiration of his contemporaries. The letters he wrote to his family, especially to his favourite daughter Meg, reveal a man of great intellectual and spiritual depth but also a very recognizably human man with a sense of humour and a tender and affectionate love for his family.

Thomas More and His Family by Rowland Lockey after a painting by Hans Holbein (Source: Wikimedia Commons). Thomas More sits in the middle, wearing his chain of office as Lord Chancellor. On his right, in red, is his father, and on his left, his son, John. On the far right of the painting is his wife, Alice, and next to her, his favourite daughter, Margaret Roper.

Thomas More Bidding His Daughter Margaret Roper Farewell by Edward Matthew Ward (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Do you want to read more about St. Thomas More’s witness to faith and the importance of conscience? Read these two articles from Salt + Light Media: “To set the world at naught”: Thomas More, John Fisher, and the role of conscience St. Thomas More and the responsibility of Christian citizenship

Related Articles:

<<