Saint Charles de Foucauld: A man in the arena

Benjamin Boivin

Thursday, May 5, 2022

Statue of Blessed Charles de Foucauld in front of the Catholic Church of Saint-Pierre-le-Jeune in Strasbourg, France. Photo credit: Rabanus Flavus on Wikimedia Commons

There are all sorts of saints. We have, of course, the classical figures of sanctity – often associated with an intense religious life of asceticism, community, and prayer, or else martyrdom – but they can sometimes be hard to identify with.

Over recent decades, these classical Christian heroes have been complemented by saints of ordinary life, so to speak – saints who are examples of the ways in which the many, not the few, are called to be reunited with God. We can think of them as working-class heroes because, indeed, the saints are our heroes.

An unexpected start for sainthood

Soon-to-be–saint Charles de Foucauld is an interesting case in holiness. In so many ways, his early life represents modern Europe at the height of its hubris. Coming from an aristocratic family, young Charles was a lacklustre student, often called lazy by his tutors. He lived a dissolute life of sensible, material satisfactions. For a long time, he was one to whom much was given yet who bore little fruit despite his remarkable abilities.

In 1876, at the age of eighteen, he enrolled in the army, which later sent him to North Africa. His experience there with the army brought him an increasing interest in geography. He also became a student of the culture of this area of the world, for which he was recognized amongst his peers.

Conversion and martyrdom

Because of his background, education, and life experience, Charles had fallen into disbelief. By 1890, however, things had changed. His faith was restored, and he chose the path of religious life in the Trappist tradition. Eventually, striving for an even more radical experience of God, he dedicated himself as a hermit.

In North Africa, Charles continued his profound inquiry into the various aspects of the local Tuareg culture and language, for which he is still remembered. He was also a powerful witness of Christ amongst those he befriended, developing a spiritual path which still today forms the basis of a number of religious communities across the world, even though his own religious life was mostly solitary.

In 1916, Charles was kidnapped and killed by tribal raiders. His death was recognized by the Church as martyrdom, leading to his beatification under Pope Benedict XVI. His coming canonization by Pope Francis was made possible after a miracle involving the unlikely survival of a young carpenter following what should have been a deadly fall of 16 metres.

Charles de Foucauld is commemorated on December 1st, the anniversary of his death, as is the custom in the Church.

A man in the arena

In some ways, Charles de Foucauld is a remarkable expression of the sanctifying power of the Faith. His early life encapsulated the optimism and bravado of his native Europe in an era of outright modernism, and yet through conversion, his whole self was elevated, not destroyed, by divine grace.

Soon-to-be–saint Charles de Foucauld is an interesting case in holiness. In so many ways, his early life represents modern Europe at the height of its hubris. Coming from an aristocratic family, young Charles was a lacklustre student, often called lazy by his tutors. He lived a dissolute life of sensible, material satisfactions. For a long time, he was one to whom much was given yet who bore little fruit despite his remarkable abilities.

In 1876, at the age of eighteen, he enrolled in the army, which later sent him to North Africa. His experience there with the army brought him an increasing interest in geography. He also became a student of the culture of this area of the world, for which he was recognized amongst his peers.

Conversion and martyrdom

Because of his background, education, and life experience, Charles had fallen into disbelief. By 1890, however, things had changed. His faith was restored, and he chose the path of religious life in the Trappist tradition. Eventually, striving for an even more radical experience of God, he dedicated himself as a hermit.

In North Africa, Charles continued his profound inquiry into the various aspects of the local Tuareg culture and language, for which he is still remembered. He was also a powerful witness of Christ amongst those he befriended, developing a spiritual path which still today forms the basis of a number of religious communities across the world, even though his own religious life was mostly solitary.

In 1916, Charles was kidnapped and killed by tribal raiders. His death was recognized by the Church as martyrdom, leading to his beatification under Pope Benedict XVI. His coming canonization by Pope Francis was made possible after a miracle involving the unlikely survival of a young carpenter following what should have been a deadly fall of 16 metres.

Charles de Foucauld is commemorated on December 1st, the anniversary of his death, as is the custom in the Church.

A man in the arena

In some ways, Charles de Foucauld is a remarkable expression of the sanctifying power of the Faith. His early life encapsulated the optimism and bravado of his native Europe in an era of outright modernism, and yet through conversion, his whole self was elevated, not destroyed, by divine grace.

American President Theodore Roosevelt, a contemporary of Charles who belonged to the Reformed Church and who was in no way a saint, is well-known for having theorized – and also embodied – the modern ideal of “the strenuous life”, that of “the man in the arena”, who fully inhabits his gifts and abilities, the man who knows and masters the world. Roosevelt was a politician, an explorer, a soldier, an historian, a conservationist, a Renaissance man of sorts, and he came to embody a spirit of discovery and optimism that makes him one of the true modern heroes.

In his very own, distinct way, we can think of Saint Charles de Foucauld as a reenchanted modern hero. He, too, led a strenuous life. He, too, was a man in the arena. But a man in the arena of God. What made him a true Christian hero, a saint, was his willingness to accept God's embrace, to submit his numerous talents and abilities to Him, and to give up his life for Him in the end, when the bell tolled.

Possible patronage

Often portrayed with his distinctive religious habit adorned with the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Charles de Foucauld has yet to be designated as a patron saint. In many ways, his life crosses usually well-defined boundaries.

He was a paradigmatic adventurer who, unlike many others in his day, respected and valued the world in which he was submerged. Because he eventually let God inhabit his somewhat rebellious and pugnacious nature, Charles would be a great patron for young men, who look for meaning, guidance, and virtue but are also often characterized by a yearning for the unknown, for adventure, for greatness.

The substance of his adventures and his taste for geography, languages, and culture would make him a good patron for those who study these things. His life as an expat would be very relevant to those who live far away from home, and his many different interests, glorified and elevated by his faith, make him an example for those who might find themselves pulled in many directions.

Photos:

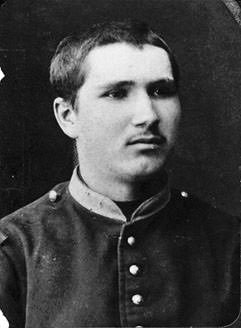

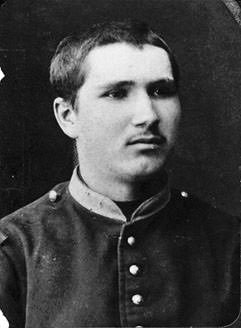

1. Charles de Foucauld at 18 years old

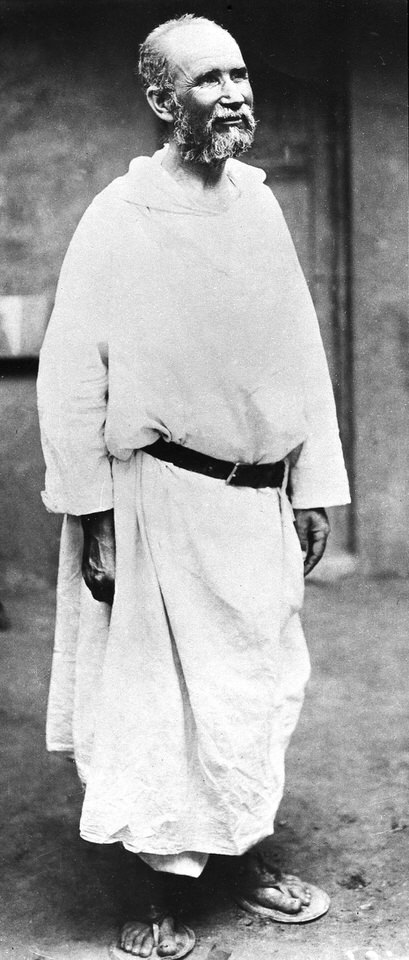

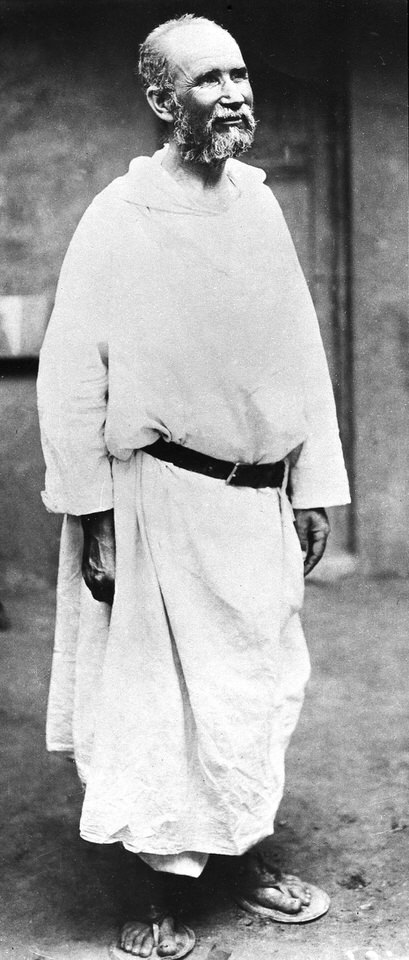

2. Last known photo of Charles de Foucauld, ca. 1915

American President Theodore Roosevelt, a contemporary of Charles who belonged to the Reformed Church and who was in no way a saint, is well-known for having theorized – and also embodied – the modern ideal of “the strenuous life”, that of “the man in the arena”, who fully inhabits his gifts and abilities, the man who knows and masters the world. Roosevelt was a politician, an explorer, a soldier, an historian, a conservationist, a Renaissance man of sorts, and he came to embody a spirit of discovery and optimism that makes him one of the true modern heroes.

In his very own, distinct way, we can think of Saint Charles de Foucauld as a reenchanted modern hero. He, too, led a strenuous life. He, too, was a man in the arena. But a man in the arena of God. What made him a true Christian hero, a saint, was his willingness to accept God's embrace, to submit his numerous talents and abilities to Him, and to give up his life for Him in the end, when the bell tolled.

Possible patronage

Often portrayed with his distinctive religious habit adorned with the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Charles de Foucauld has yet to be designated as a patron saint. In many ways, his life crosses usually well-defined boundaries.

He was a paradigmatic adventurer who, unlike many others in his day, respected and valued the world in which he was submerged. Because he eventually let God inhabit his somewhat rebellious and pugnacious nature, Charles would be a great patron for young men, who look for meaning, guidance, and virtue but are also often characterized by a yearning for the unknown, for adventure, for greatness.

The substance of his adventures and his taste for geography, languages, and culture would make him a good patron for those who study these things. His life as an expat would be very relevant to those who live far away from home, and his many different interests, glorified and elevated by his faith, make him an example for those who might find themselves pulled in many directions.

Photos:

1. Charles de Foucauld at 18 years old

2. Last known photo of Charles de Foucauld, ca. 1915

Soon-to-be–saint Charles de Foucauld is an interesting case in holiness. In so many ways, his early life represents modern Europe at the height of its hubris. Coming from an aristocratic family, young Charles was a lacklustre student, often called lazy by his tutors. He lived a dissolute life of sensible, material satisfactions. For a long time, he was one to whom much was given yet who bore little fruit despite his remarkable abilities.

In 1876, at the age of eighteen, he enrolled in the army, which later sent him to North Africa. His experience there with the army brought him an increasing interest in geography. He also became a student of the culture of this area of the world, for which he was recognized amongst his peers.

Conversion and martyrdom

Because of his background, education, and life experience, Charles had fallen into disbelief. By 1890, however, things had changed. His faith was restored, and he chose the path of religious life in the Trappist tradition. Eventually, striving for an even more radical experience of God, he dedicated himself as a hermit.

In North Africa, Charles continued his profound inquiry into the various aspects of the local Tuareg culture and language, for which he is still remembered. He was also a powerful witness of Christ amongst those he befriended, developing a spiritual path which still today forms the basis of a number of religious communities across the world, even though his own religious life was mostly solitary.

In 1916, Charles was kidnapped and killed by tribal raiders. His death was recognized by the Church as martyrdom, leading to his beatification under Pope Benedict XVI. His coming canonization by Pope Francis was made possible after a miracle involving the unlikely survival of a young carpenter following what should have been a deadly fall of 16 metres.

Charles de Foucauld is commemorated on December 1st, the anniversary of his death, as is the custom in the Church.

A man in the arena

In some ways, Charles de Foucauld is a remarkable expression of the sanctifying power of the Faith. His early life encapsulated the optimism and bravado of his native Europe in an era of outright modernism, and yet through conversion, his whole self was elevated, not destroyed, by divine grace.

Soon-to-be–saint Charles de Foucauld is an interesting case in holiness. In so many ways, his early life represents modern Europe at the height of its hubris. Coming from an aristocratic family, young Charles was a lacklustre student, often called lazy by his tutors. He lived a dissolute life of sensible, material satisfactions. For a long time, he was one to whom much was given yet who bore little fruit despite his remarkable abilities.

In 1876, at the age of eighteen, he enrolled in the army, which later sent him to North Africa. His experience there with the army brought him an increasing interest in geography. He also became a student of the culture of this area of the world, for which he was recognized amongst his peers.

Conversion and martyrdom

Because of his background, education, and life experience, Charles had fallen into disbelief. By 1890, however, things had changed. His faith was restored, and he chose the path of religious life in the Trappist tradition. Eventually, striving for an even more radical experience of God, he dedicated himself as a hermit.

In North Africa, Charles continued his profound inquiry into the various aspects of the local Tuareg culture and language, for which he is still remembered. He was also a powerful witness of Christ amongst those he befriended, developing a spiritual path which still today forms the basis of a number of religious communities across the world, even though his own religious life was mostly solitary.

In 1916, Charles was kidnapped and killed by tribal raiders. His death was recognized by the Church as martyrdom, leading to his beatification under Pope Benedict XVI. His coming canonization by Pope Francis was made possible after a miracle involving the unlikely survival of a young carpenter following what should have been a deadly fall of 16 metres.

Charles de Foucauld is commemorated on December 1st, the anniversary of his death, as is the custom in the Church.

A man in the arena

In some ways, Charles de Foucauld is a remarkable expression of the sanctifying power of the Faith. His early life encapsulated the optimism and bravado of his native Europe in an era of outright modernism, and yet through conversion, his whole self was elevated, not destroyed, by divine grace.

American President Theodore Roosevelt, a contemporary of Charles who belonged to the Reformed Church and who was in no way a saint, is well-known for having theorized – and also embodied – the modern ideal of “the strenuous life”, that of “the man in the arena”, who fully inhabits his gifts and abilities, the man who knows and masters the world. Roosevelt was a politician, an explorer, a soldier, an historian, a conservationist, a Renaissance man of sorts, and he came to embody a spirit of discovery and optimism that makes him one of the true modern heroes.

American President Theodore Roosevelt, a contemporary of Charles who belonged to the Reformed Church and who was in no way a saint, is well-known for having theorized – and also embodied – the modern ideal of “the strenuous life”, that of “the man in the arena”, who fully inhabits his gifts and abilities, the man who knows and masters the world. Roosevelt was a politician, an explorer, a soldier, an historian, a conservationist, a Renaissance man of sorts, and he came to embody a spirit of discovery and optimism that makes him one of the true modern heroes.Related Articles:

<<