Romero's Transformation

Salt + Light Media

Friday, March 16, 2018

CNS photo/Rhina Guidos

Romero's Transformation: By Alicia Ambrosio

In a small park in Ciudad Barrios, the shouts and cheers of a group of children playing soccer echo through a park. Across the street another child, a skinny little boy with an air of seriousness about him, walks along with his father. He hears the happy ruckus in the park and glances over at the game in play, but is not interested in joining in. This 12 year old, Oscar, is quite content by his father’s side. His father, Santos Romero, is the town telegraph operator and Oscar is helping deliver telegrams that arrived this morning. Oscar won’t be able to help his father much longer. His father has arranged for him to begin training with a local carpenter. This will ease the strain on the family’s resources and give Oscar the skills to secure a good paying job one day.

Oscar, however, never becomes a carpenter. He works as an apprentice for one year and then his life changes completely. A priest comes to town to visit the local parish and Oscar, who has always been attached to the life of the church, realizes his heart’s deepest desire is to be a priest. His father does not like the idea, but eventually he relents and agrees to let Oscar enter the seminary.

Fr. Oscar Romero

By the time Oscar Romero is ordained to the priesthood in 1942 he has studied in El Salvador and Rome. The time in Rome deepens his attachment to the structures of the institutional church but also his faithfulness to the pope and the magisterium of the Church. When Fr. Romero returns to El Salvador this dual attachment leads him to maintain the status quo, but at the same time paves the way for his transformation into an outspoken critic of the injustice and corruption that are rampant in the country.

Fr. Romero gains a reputation as a “conservative”, traditional-minded priest in the diocese of San Miguel in the 1940s. He runs the diocesan newspaper which, under his leadership, takes on a pro-pope, pro-magisterium editorial line. This is interpreted by church and government leaders as a sign that Fr. Romero is quite happy to simply do his work and not rock the boat.

Bishop Romero and the 1970s

By the 1970s when Fr. Romero is named auxiliary bishop of San Salvador, he has spent years ministering to Salvadoran Catholics from all walks of life. He has seen the startling conditions in which the poorest, most faithful Catholics live and the comfort that the well off Salvadoran Catholics enjoy. Coming from a humble background himself, Romero is not untouched by the living and working conditions of his parishioners. Still, he is shy and introspective and is more likely to meditate on what he sees rather than denounce it publicly.

However tension between the Salvadoran working class and the elite landowners is on the rise through the 1960s and 70s. There is an increase in left wing guerilla groups trying to wrestle power away from the ruling class. At the same time there is an increase in activity by right wing paramilitary groups.

Amid this tension many priests are putting the church’s preferential option for the poor into action: living side by side with the campesinos, helping them ask for fair wages, and in some cases getting involved with guerilla groups. Some priests, like Romero’s friend Fr. Rutilio Grande, try to empower the campesinos by forming their faith so they can have a personal relationship with Christ, who is freedom.

This distinction is not clear to the government and paramilitary groups. Any priest working with the poor is seen as a threat to the establishment. In 1977, the same year that Romero is named Archbishop of San Salvador, Fr. Grande is ambushed and killed on his way to celebrate Mass in a rural parish.

The Death of Rutilio Grande

For Romero the violent death of his seminary classmate and lifelong Jesuit friend is a moment of awakening. When he learns of Grande’s death Romero runs to the home where the murdered priest’s body has been taken. There he witnesses a scene he never imagined: the landless campesinos Fr. Grande worked with arrive in droves to keep vigil over his body. They mourn him as one would mourn their father, and yet they have hope. They make no secret of the fact that they believe Jesus will send someone else to help them.

As he has until now, Archbishop Romero meditates on what he sees. This time, however, he feels that God is calling him not only to continue Grande’s work with the poor, disenfranchised workers but also to use his position as archbishop of the nation’s capital to be a voice for the voiceless.

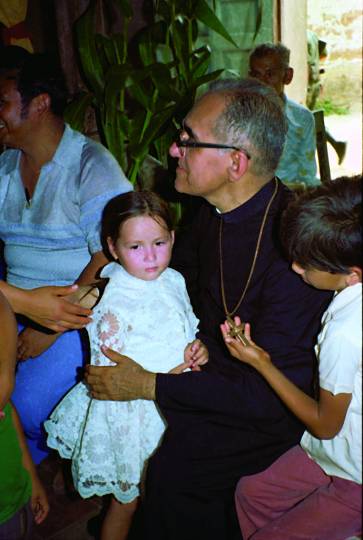

Photo Credit: Archbishop Romero inside the church at San Antonio Los Ranchos in Chalatenango, El Salvador, 1979. CNS photo/Octavio Duran

This post was an excerpt from Salt+Light’s Winter 2015 Magazine

Oscar, however, never becomes a carpenter. He works as an apprentice for one year and then his life changes completely. A priest comes to town to visit the local parish and Oscar, who has always been attached to the life of the church, realizes his heart’s deepest desire is to be a priest. His father does not like the idea, but eventually he relents and agrees to let Oscar enter the seminary.

Fr. Oscar Romero

By the time Oscar Romero is ordained to the priesthood in 1942 he has studied in El Salvador and Rome. The time in Rome deepens his attachment to the structures of the institutional church but also his faithfulness to the pope and the magisterium of the Church. When Fr. Romero returns to El Salvador this dual attachment leads him to maintain the status quo, but at the same time paves the way for his transformation into an outspoken critic of the injustice and corruption that are rampant in the country.

Fr. Romero gains a reputation as a “conservative”, traditional-minded priest in the diocese of San Miguel in the 1940s. He runs the diocesan newspaper which, under his leadership, takes on a pro-pope, pro-magisterium editorial line. This is interpreted by church and government leaders as a sign that Fr. Romero is quite happy to simply do his work and not rock the boat.

Bishop Romero and the 1970s

By the 1970s when Fr. Romero is named auxiliary bishop of San Salvador, he has spent years ministering to Salvadoran Catholics from all walks of life. He has seen the startling conditions in which the poorest, most faithful Catholics live and the comfort that the well off Salvadoran Catholics enjoy. Coming from a humble background himself, Romero is not untouched by the living and working conditions of his parishioners. Still, he is shy and introspective and is more likely to meditate on what he sees rather than denounce it publicly.

However tension between the Salvadoran working class and the elite landowners is on the rise through the 1960s and 70s. There is an increase in left wing guerilla groups trying to wrestle power away from the ruling class. At the same time there is an increase in activity by right wing paramilitary groups.

Amid this tension many priests are putting the church’s preferential option for the poor into action: living side by side with the campesinos, helping them ask for fair wages, and in some cases getting involved with guerilla groups. Some priests, like Romero’s friend Fr. Rutilio Grande, try to empower the campesinos by forming their faith so they can have a personal relationship with Christ, who is freedom.

This distinction is not clear to the government and paramilitary groups. Any priest working with the poor is seen as a threat to the establishment. In 1977, the same year that Romero is named Archbishop of San Salvador, Fr. Grande is ambushed and killed on his way to celebrate Mass in a rural parish.

The Death of Rutilio Grande

For Romero the violent death of his seminary classmate and lifelong Jesuit friend is a moment of awakening. When he learns of Grande’s death Romero runs to the home where the murdered priest’s body has been taken. There he witnesses a scene he never imagined: the landless campesinos Fr. Grande worked with arrive in droves to keep vigil over his body. They mourn him as one would mourn their father, and yet they have hope. They make no secret of the fact that they believe Jesus will send someone else to help them.

As he has until now, Archbishop Romero meditates on what he sees. This time, however, he feels that God is calling him not only to continue Grande’s work with the poor, disenfranchised workers but also to use his position as archbishop of the nation’s capital to be a voice for the voiceless.

Photo Credit: Archbishop Romero inside the church at San Antonio Los Ranchos in Chalatenango, El Salvador, 1979. CNS photo/Octavio Duran

This post was an excerpt from Salt+Light’s Winter 2015 Magazine

Oscar, however, never becomes a carpenter. He works as an apprentice for one year and then his life changes completely. A priest comes to town to visit the local parish and Oscar, who has always been attached to the life of the church, realizes his heart’s deepest desire is to be a priest. His father does not like the idea, but eventually he relents and agrees to let Oscar enter the seminary.

Fr. Oscar Romero

By the time Oscar Romero is ordained to the priesthood in 1942 he has studied in El Salvador and Rome. The time in Rome deepens his attachment to the structures of the institutional church but also his faithfulness to the pope and the magisterium of the Church. When Fr. Romero returns to El Salvador this dual attachment leads him to maintain the status quo, but at the same time paves the way for his transformation into an outspoken critic of the injustice and corruption that are rampant in the country.

Fr. Romero gains a reputation as a “conservative”, traditional-minded priest in the diocese of San Miguel in the 1940s. He runs the diocesan newspaper which, under his leadership, takes on a pro-pope, pro-magisterium editorial line. This is interpreted by church and government leaders as a sign that Fr. Romero is quite happy to simply do his work and not rock the boat.

Bishop Romero and the 1970s

By the 1970s when Fr. Romero is named auxiliary bishop of San Salvador, he has spent years ministering to Salvadoran Catholics from all walks of life. He has seen the startling conditions in which the poorest, most faithful Catholics live and the comfort that the well off Salvadoran Catholics enjoy. Coming from a humble background himself, Romero is not untouched by the living and working conditions of his parishioners. Still, he is shy and introspective and is more likely to meditate on what he sees rather than denounce it publicly.

However tension between the Salvadoran working class and the elite landowners is on the rise through the 1960s and 70s. There is an increase in left wing guerilla groups trying to wrestle power away from the ruling class. At the same time there is an increase in activity by right wing paramilitary groups.

Amid this tension many priests are putting the church’s preferential option for the poor into action: living side by side with the campesinos, helping them ask for fair wages, and in some cases getting involved with guerilla groups. Some priests, like Romero’s friend Fr. Rutilio Grande, try to empower the campesinos by forming their faith so they can have a personal relationship with Christ, who is freedom.

This distinction is not clear to the government and paramilitary groups. Any priest working with the poor is seen as a threat to the establishment. In 1977, the same year that Romero is named Archbishop of San Salvador, Fr. Grande is ambushed and killed on his way to celebrate Mass in a rural parish.

The Death of Rutilio Grande

For Romero the violent death of his seminary classmate and lifelong Jesuit friend is a moment of awakening. When he learns of Grande’s death Romero runs to the home where the murdered priest’s body has been taken. There he witnesses a scene he never imagined: the landless campesinos Fr. Grande worked with arrive in droves to keep vigil over his body. They mourn him as one would mourn their father, and yet they have hope. They make no secret of the fact that they believe Jesus will send someone else to help them.

As he has until now, Archbishop Romero meditates on what he sees. This time, however, he feels that God is calling him not only to continue Grande’s work with the poor, disenfranchised workers but also to use his position as archbishop of the nation’s capital to be a voice for the voiceless.

Photo Credit: Archbishop Romero inside the church at San Antonio Los Ranchos in Chalatenango, El Salvador, 1979. CNS photo/Octavio Duran

This post was an excerpt from Salt+Light’s Winter 2015 Magazine

Oscar, however, never becomes a carpenter. He works as an apprentice for one year and then his life changes completely. A priest comes to town to visit the local parish and Oscar, who has always been attached to the life of the church, realizes his heart’s deepest desire is to be a priest. His father does not like the idea, but eventually he relents and agrees to let Oscar enter the seminary.

Fr. Oscar Romero

By the time Oscar Romero is ordained to the priesthood in 1942 he has studied in El Salvador and Rome. The time in Rome deepens his attachment to the structures of the institutional church but also his faithfulness to the pope and the magisterium of the Church. When Fr. Romero returns to El Salvador this dual attachment leads him to maintain the status quo, but at the same time paves the way for his transformation into an outspoken critic of the injustice and corruption that are rampant in the country.

Fr. Romero gains a reputation as a “conservative”, traditional-minded priest in the diocese of San Miguel in the 1940s. He runs the diocesan newspaper which, under his leadership, takes on a pro-pope, pro-magisterium editorial line. This is interpreted by church and government leaders as a sign that Fr. Romero is quite happy to simply do his work and not rock the boat.

Bishop Romero and the 1970s

By the 1970s when Fr. Romero is named auxiliary bishop of San Salvador, he has spent years ministering to Salvadoran Catholics from all walks of life. He has seen the startling conditions in which the poorest, most faithful Catholics live and the comfort that the well off Salvadoran Catholics enjoy. Coming from a humble background himself, Romero is not untouched by the living and working conditions of his parishioners. Still, he is shy and introspective and is more likely to meditate on what he sees rather than denounce it publicly.

However tension between the Salvadoran working class and the elite landowners is on the rise through the 1960s and 70s. There is an increase in left wing guerilla groups trying to wrestle power away from the ruling class. At the same time there is an increase in activity by right wing paramilitary groups.

Amid this tension many priests are putting the church’s preferential option for the poor into action: living side by side with the campesinos, helping them ask for fair wages, and in some cases getting involved with guerilla groups. Some priests, like Romero’s friend Fr. Rutilio Grande, try to empower the campesinos by forming their faith so they can have a personal relationship with Christ, who is freedom.

This distinction is not clear to the government and paramilitary groups. Any priest working with the poor is seen as a threat to the establishment. In 1977, the same year that Romero is named Archbishop of San Salvador, Fr. Grande is ambushed and killed on his way to celebrate Mass in a rural parish.

The Death of Rutilio Grande

For Romero the violent death of his seminary classmate and lifelong Jesuit friend is a moment of awakening. When he learns of Grande’s death Romero runs to the home where the murdered priest’s body has been taken. There he witnesses a scene he never imagined: the landless campesinos Fr. Grande worked with arrive in droves to keep vigil over his body. They mourn him as one would mourn their father, and yet they have hope. They make no secret of the fact that they believe Jesus will send someone else to help them.

As he has until now, Archbishop Romero meditates on what he sees. This time, however, he feels that God is calling him not only to continue Grande’s work with the poor, disenfranchised workers but also to use his position as archbishop of the nation’s capital to be a voice for the voiceless.

Photo Credit: Archbishop Romero inside the church at San Antonio Los Ranchos in Chalatenango, El Salvador, 1979. CNS photo/Octavio Duran

This post was an excerpt from Salt+Light’s Winter 2015 MagazineRelated Articles:

<<