Pope Benedict XVI: A Lifelong Commitment to Ecumenism | One Body

Sr. Donna Geernaert, SC

Tuesday, January 31, 2023

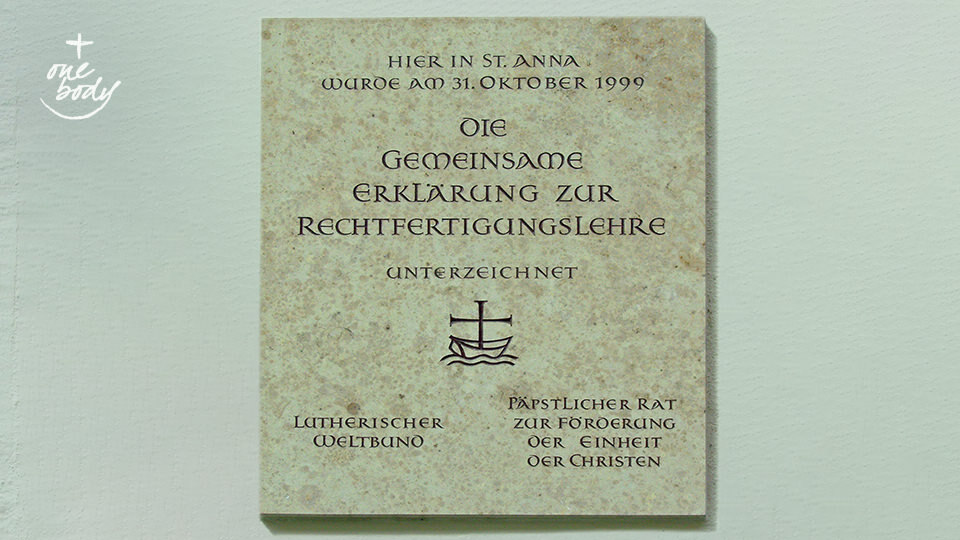

Plaque commemorating the joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, St. Anne's Church, Augsburg. (2022, December 28). Wikimedia Commons.

Pope Benedict XVI: A Lifelong Commitment to Ecumenism

by Sr. Donna Geernaert, SC

One day after his election to the papacy on April 19, 2005, Pope Benedict XVI addressed the College of Cardinals. He affirmed his commitment to the ecumenical agenda of his predecessor, Pope John Paul II, and identified his primary task as the impelling duty “to work tirelessly to rebuild the full and visible unity of all Christ’s followers." He stated his readiness “to do everything in his power to promote the fundamental cause of ecumenism,” as well as his determination “to encourage every initiative that seems appropriate for promoting contacts and understanding with the representatives of the different Churches and Ecclesial Communities.” At the time of his death on December 31, 2022, tributes from ecumenical partners around the world testified to his fidelity to these commitments made at beginning of his papacy. While the late pope had formed strong bonds of friendship and esteem with leaders of Orthodox and Anglican Churches, his longest ecumenical experience was forged in the area of Catholic-Lutheran relations. Joseph Ratzinger came from a country at the centre of the 16th-century Reformation, with a roughly equal number of Catholics and Protestants, and had read all of Luther’s pre-Reformation works before entering university. Through teaching and dialogue with Lutheran colleagues during his time as a professor in Germany, he grew in awareness of the contributions of Lutheranism to Christianity. As Archbishop of Cologne he served with Lutheran Bishop Eduard Lohse as co-chair of a dialogue commission, and in the 1970s he expressed interest in declaring the Augsburg Confession — a key Lutheran text — a Catholic document. His contribution to the historic Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification may well be his most significant ecumenical achievement.Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification: an Ecumenical Milestone

In the 16th century, Lutherans and Roman Catholics were involved in a dispute about certain aspects of the New Testament teaching on justification, how Christ’s saving action is received by those who are saved. Where Lutheran teaching maintains that sinners are justified by faith alone through the righteousness of Christ which is ascribed to them without works, the Catholic position affirms that justification empowers Christians to do good works by renewing and sanctifying them. For both parties, the truth of the Gospel was at stake, which led them to issue mutual condemnations that continue to influence how each Church sees the other. Over several years of ecumenical dialogue on this central Reformation issue, real progress was made and participants began to ask whether the beliefs that were condemned in the heat of controversy are actually held today. This question was central to a study published in 1986 by a working group of Protestant and Catholic theologians in Germany entitled, The Condemnations of the Reformation Era – Do They Still Divide? The formal answer to the question posed in the title of the 1986 book was given in Augsburg, Germany on October 31, 1999 when representatives of the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) and the Vatican met to sign the JDDJ. The consensus statement in the Joint Declaration reads: “Together we confess: By grace alone, in faith in Christ’s saving work and not because of any merit on our part, we are accepted by God and receive the Holy Spirit, who renews our hearts while equipping and calling us to good works.” For Lutherans, the doctrine of justification is the article on which the church stands or falls, the crux of all the disputes. An important topic in official Lutheran/Roman Catholic dialogues from the beginning, a study of various dialogue reports showed a high degree of agreement in both approach and conclusions. In June 1993, members of the LWF and the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (PCPCU) agreed to summarize these dialogue results so that the two churches could make decisions about the degree of agreement that had been achieved, and consider the feasibility of developing a declaration concerning the inapplicability of the mutual condemnations. In February 1995, a draft of the Joint Declaration was prepared by the LWF and the PCPCU. After a preliminary circulation, the text was revised in June 1996 and again circulated. At the request of the LWF, some sections of the text were revised and a Final Proposal of the Joint Declaration was published in February 1997. On June 16, 1998, following worldwide consultation of its member churches, the LWF Council unanimously approved the Joint Declaration. Nine days later, the Vatican issued its official response in a three-part statement consisting of a “declaration” which affirmed the existence of a consensus in basic truths of the doctrine of justification, some additional comments or “clarifications” which identified a number of specific points where divergences remain, and “prospects for the future” which expressed the hope for further studies to clarify the divergences that still exist. For Lutherans and many others, the Vatican response appeared to question the validity of the consensus claimed in the Joint Declaration and thus, to place its assertion of the non-applicability of the 16th century doctrinal condemnations in doubt.Signing of the JDDJ: Enter Cardinal Ratzinger

Catholic leaders, including Pope John Paul II and PCPCU Prefect Cardinal Edward Cassidy, consistently stated that the Vatican response affirmed the consensus reached in the Joint Declaration. However, it was clear that an additional step would be needed before the document could be signed. It was at this point that Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, then Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, intervened. This was an interesting intervention since many saw him as the source of the problem and even claimed that he wanted to undermine the agreement. In a letter to the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine on July 14, 1998, Cardinal Ratzinger protested that he had sought closer relations with Lutherans since his days as a seminarian and said that to scuttle the dialogue would be to “deny myself.” On November 3, 1998, a small ad hoc working group was convened by Lutheran Bishop Johannes Hanselmann. Ratzinger played a key role in the discussions; the group even met at the home of his brother Georg in Regensburg, Bavaria. At the meeting, Cardinal Ratzinger responded to specific Lutheran concerns: he affirmed his understanding that the goal of the ecumenical process is unity in diversity rather than structural reintegration and acknowledged the LWF’s authority to reach agreement with the Vatican. He agreed that while Christians are obliged to do good works, justification and final judgement remain God’s gracious acts. This meeting enabled the development in the late spring of 1999 of an Official Common Statement and an Annex to ensure both the LWF and the Vatican had the same understanding of the signing. The Official Common Statement clarified the consensus which was reached and identified areas for further study, such as the biblical foundations of justification and issues identified in article 43 of the Joint Declaration. The Annex reiterated the consensus achieved and confirmed that the “condemnations of former times do not apply to the Catholic and Lutheran doctrines of justification as they are presented in the Joint Declaration.” It discussed the way in which justification may be seen as a touchstone for the Christian faith, affirmed the equal rights of the participants, and stated that “each partner respects the other partner’s ordered process of reaching doctrinal decisions.”Follow-up to the Signing of the JDDJ

Since the signing of the JDDJ, attention has been given to clarifying specific points that it identified. In this context, a working group of exegetes and experts from Catholic, Lutheran, Methodist, and Reformed traditions published its study document on The Biblical Foundations of the Doctrine of Justification in 2012. A trilateral dialogue between Catholics, Lutherans and Mennonites completed its study on baptism in September 2017. To mark the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the beginning of the Reformation in 2017, the Lutheran-Roman Catholic Commission on Unity published a joint document, From Conflict to Communion, inviting reflection on the divisive events of the past from the perspective of the Gospel call to repentance and reform in the search for Christian unity. The signing of the JDDJ marks a significant breakthrough in the search for Christian unity. Not only is it the first time the Catholic Church has entered into a joint declaration with any of the churches of the West, it also deals with a theological issue recognized as key to the 16th-century Reformation divisions. Perhaps the most sustainable and important consequence of the signing of the JDDJ is that Catholic relations with Lutherans have gained a new quality and intensity which are rather different from relations with other Reformation era churches.The significance of the JDDJ is further enhanced by its extension to other Christian Churches. To date, the World Methodist Council, (2006) the Anglican Consultative Council, (2016) and the World Communion of Reformed Churches (2017) have expressed their adherence with the substance of the JDDJ. In March 2019, representatives of Anglican, Catholic, Lutheran, Methodist, and Reformed Churches met at the University of Notre Dame to mark the twentieth anniversary of the signing of the JDDJ and to explore some implications of their common affiliation. A statement issued at the end of the conference identified specific affirmations and commitments to common witness, as well as an agreement to establish a Steering Committee to promote and monitor the process of developing relationships among the adherents to the JDDJ. It is important to note two differing groups that have yet to sign the Joint Declaration. On the one hand, there are Lutheran Churches that are not members of the LWF that continue to dispute the JDDJ’s claim to have achieved consensus on the doctrine of justification. On the other hand, recent studies by Baptist scholars have found the JDDJ consistent with their Church’s understanding of justification and expressed the hope that the Baptist World Alliance would also signify its adherence to the consensus.

The JDDJ concludes with an important affirmation: “Our consensus in basic truths of the doctrine of justification must come to influence the life and teaching of our Churches.” (#43) Ttraditional interpretations of the doctrine of justification may seem quite theoretical and somewhat remote from contemporary concerns. But the Joint Declaration leads us to ask, is there something to be learned from Luther’s witness to the liberating promise of God’s grace, and his focus on a theology of the cross? Might that help the Churches develop, together, a more consistent and effective response to some of today’s questions? On the tenth anniversary of the signing of the JDDJ, Pope Benedict XVI devoted a portion of his weekly Angelus address to identifying the fundamental truths of the doctrine of justification as those "which lead us to the heart of the Gospel itself and to the essential questions of our life.” In brief, “our existence is inscribed on the horizon of grace.... We live by the grace of God and are called to respond to his gift; all this frees us from fear and instills hope and courage in a world full of uncertainty, uneasiness and suffering.”

These same themes were taken up in his 2011 Apostolic Journey to Germany. At a meeting with the Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany at the former Augustinian convent in Erfurt, he praised Luther’s quest to understand how to receive the grace of God as “the deep passion and driving force of his whole life’s journey.” At the evening prayer service in the same location, he disappointed those who were hoping for a “special gift” in terms of a release from restrictions on reception of communion in inter-church families, but reiterated his understanding that “commitment to justice throughout the world” is integral to Christian faith and living the ecumenical task. He stated: “Unity grows not by the weighing of benefits and drawbacks but by entering more deeply into the faith in our thoughts and our lives.”

Throughout his lifetime, Pope Benedict XVI was a committed and principled ecumenist. In today’s increasingly violent and divided world, his witness to the ongoing search for Christian unity is both an invitation and a challenge.

Sr. Dr. Donna Geernaert, SC, served for 18 years in promoting ecumenical and interfaith relations for the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. She has been a staff member, consultant, and member of numerous multilateral and bilateral theological dialogues in Canada as well as internationally.

Sr. Dr. Donna Geernaert, SC, served for 18 years in promoting ecumenical and interfaith relations for the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. She has been a staff member, consultant, and member of numerous multilateral and bilateral theological dialogues in Canada as well as internationally.

Related Articles:

<<