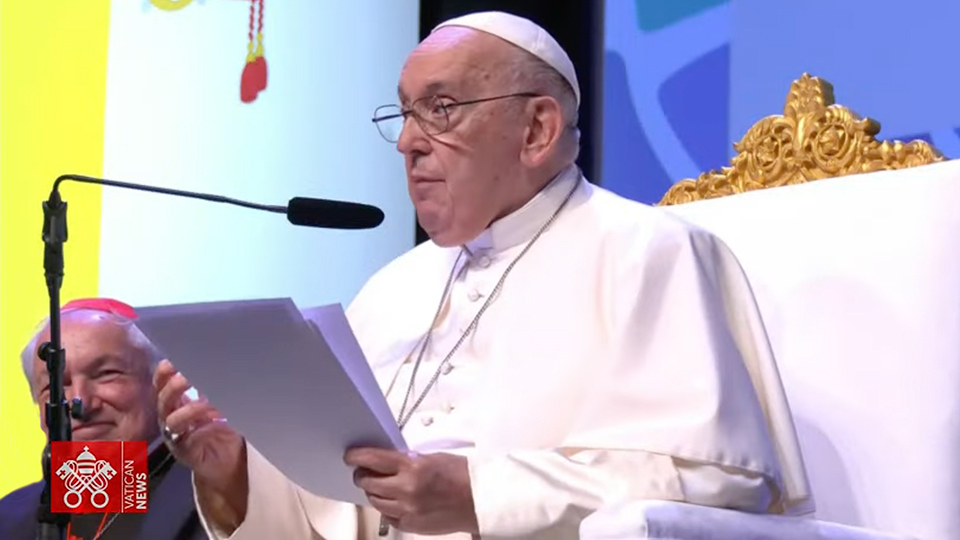

Final Session of the Rencontres Méditerranéennes: Address of His Holiness

Pope Francis

Saturday, September 23, 2023

The centrepiece of Pope Francis' Apostolic Visit to Marseille was his address to conclude the Rencontres Méditerranéennes, a semi-regular gathering of bishops, young people, artists, and activists from southern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. He told the gathering that "amidst today’s sea of conflicts, we are here to enhance the contribution of the Mediterranean, so that it can return to being a laboratory of peace. For this is its vocation, to be a place where different countries and realities can encounter each other on the basis of the humanity we all share, and not on the basis of contrasting ideologies."Read the full text of his address below:

Final Session of the Rencontres Méditerranéennes Address of His Holiness

Palais du Pharo, Marseille Saturday, 23 September, 2023

Mr President,

Dear brother Bishops,

Distinguished Mayors and Authorities representing cities and territories bordered by the Mediterranean Sea,

Dear friends all!

I offer my cordial greetings and I am grateful to each of you for having accepted the invitation of Cardinal Aveline to participate in these meetings. Thank you for your work and the valuable reflections that you shared. After Bari and Florence, the journey in service to the Mediterranean peoples is moving forward: here also, Church and civil leaders are gathered not to deal with mutual interests, but animated by the desire to care for men and women. Thank you for involving young people, who are the present and future of the Church and society.

Marseille is a very ancient city. Founded by Greek sailors who came from Asia Minor, legend traces it back to a love story between an emigrant sailor and a native princess. From its beginnings, it has displayed a diverse and cosmopolitan character: it welcomes the riches of the sea and gives a homeland to those who no longer have one. Marseilles tells us that, despite difficulties, coexistence is possible and is a source of joy. On the map, it almost seems to draw a smile between Nice and Montpellier. I like to think of it that way: Marseilles as “the smile of the Mediterranean”. So I want to offer you some thoughts centred around three aspects that characterize Marseille, three symbols: the sea, the port and the lighthouse.

1. The sea. A tide of peoples has made this city a mosaic of hope, with its great multiethnic and multicultural tradition, represented by the more than sixty Consulates in its territory. Marseille is both a diverse and distinct city, for it is its diversity, the fruit of an encounter with the world, that makes its history distinct. Nowadays we often hear that Mediterranean history is an intertwining of conflicts between different civilizations, religions, and visions. Let us not ignore the problems that exist, yet let us not be misled: the exchanges that have taken place between peoples have made the Mediterranean the cradle of civilization, a sea overflowing with treasures, to the point that, as a great French historian wrote, it is “not one landscape, but countless landscapes. Not one sea, but a succession of seas,… for millennia everything has flowed into it, complicating and enriching its history” (Fernand Braudel, La Méditerranée, Paris 1985, 16). Our sea (mare nostrum) is a place of encounter: among the Abrahamic religions; among Greek, Latin and Arabic thought; among science, philosophy and law; and among many other realities. It has conveyed to the world the lofty value of the human being, endowed with freedom, open to the truth and in need of salvation, who sees the world as a wonder to be discovered and as a garden to be inhabited, under the imprint of a God who makes covenants with men and women.

A great mayor saw in the Mediterranean not a question of conflict but a response of peace, indeed “the beginning and foundation of peace among all the nations of the world” (Giorgio La Pira, Remarks at the Conclusion of the First Mediterranean Colloquium, 6 October 1958). He said: “The answer… is possible if we consider the common and, so to speak, permanent vocation that Providence assigned in the past, assigns in the present and, in a certain sense, will assign in the future to the peoples and nations who live on the shores of this mysterious enlarged Lake of Tiberias that is the Mediterranean” (Address at the Opening of the First Mediterranean Colloquium, 3 October 1958). At the time of Christ, the Lake of Tiberias, or the Sea of Galilee, had a concentration of various populations, beliefs and traditions. Precisely there, in “Galilee of the Gentiles” (cf. Matthew 4:15), crossed by the Sea Route, the greater part of Jesus’ public life took place. A multifaceted and in many ways unstable context was the place for the universal proclamation of the Beatitudes, in the name of a God who is Father of all, who “makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust” (Matthew 5:45). This was also an invitation to broaden the frontiers of the heart, overcoming ethnic and cultural barriers. Here then is the answer that comes from the Mediterranean: this perennial Sea of Galilee urges us to oppose the divisiveness of conflicts with the “coexistence of differences” (Tonino Bello, Benedette inquietudini, Milan 2001, 73). Our sea, at the crossroads of North and South, East and West, brings together the challenges of the whole world, as the “five shores” on which you have reflected bear witness: North Africa, the Near East, the Black and Aegean Seas, the Balkans and Latin Europe. It is an outpost of challenges that concern everyone: let us think of the climate, with the Mediterranean representing a hotspot where changes are felt more quickly. How important it is to safeguard the Mediterranean patchwork, a unique treasure-trove of biodiversity! In short, this sea, an environment that offers a unique approach to complexity, is a “mirror of the world” and bears within itself a global vocation to fraternity, a unique vocation and the only way to prevent and overcome conflict.

Brothers and sisters, amidst today’s sea of conflicts, we are here to enhance the contribution of the Mediterranean, so that it can return to being a laboratory of peace. For this is its vocation, to be a place where different countries and realities can encounter each other on the basis of the humanity we all share, and not on the basis of contrasting ideologies. Indeed, the Mediterranean expresses a way of thinking that is not uniform and ideological, but multifaceted and consistent with the way things are; a vital, open and accommodating way of thinking, one that is communitarian, which is the correct word. How greatly we need this at the present juncture, when antiquated and belligerent nationalisms want to make the dream of the community of nations fade! Yet – let us remember this – with weapons we make war, not peace, and with greed for power we always return to the past, rather than building the future.

Where should we begin, then, in order for peace to take root? On the banks of the Sea of Galilee, Jesus began by giving hope to the poor and proclaiming them blessed: he listened to their needs, healed their wounds and above all announced to them the good news of the Kingdom. We need to start again from there, from the often silent cry of the least among us, not from the more fortunate ones who have no need of help yet still raise their voices. Let us, the Church and civil society, start anew by listening to the poor who “should be embraced, not counted” (Primo Mazzolari, La parola ai poveri, Bologna 2016, 39), for they are faces, not numbers. The change of direction in our communities lies in treating them as brothers and sisters whose stories we know, not as troublesome problems or chasing them away, sending them home; it lies in welcoming them, not hiding them; in integrating them, not evicting them; in giving them dignity. I wish to repeat that Marseilles is the capital of integrating peoples. You can be proud of this! Today the sea of human coexistence is polluted by instability, which even assails beautiful Marseille. Where there is instability there is crime. Where there is lack of work together with material, educational, cultural, and religious poverty, the path is opened up for gangs and illicit trafficking. The commitment of institutions alone is not enough, we need a jolt of conscience to say “no” to lawlessness and “yes” to solidarity, which is not a drop in the ocean, but the indispensable element for purifying its waters.

Indeed, the real social evil is not so much the increase of problems, but the decrease of care. Who nowadays becomes a neighbour to the young people left to themselves, who are easy prey for crime and prostitution? Who is taking care of them? Who is close to people enslaved by work that should make them freer? Who cares for the frightened families, afraid of the future and of bringing children into the world? Who listens to the groaning of our isolated elderly brothers and sisters, who, instead of being appreciated, are pushed aside, under the false pretenses of a supposedly dignified and “sweet” death that is more “salty” than the waters of the sea? Who thinks of the unborn children, rejected in the name of a false right to progress, which is instead a retreat into the selfish needs of the individual? Today we see the tragedy of confusing children for animals. My secretary told me that as he passed through Saint Peter’s Square he saw some women carrying children in prams... but they were not children, they were dogs! This confusion tells us something ominous. Who looks with compassion beyond their own shores to hear the cry of pain rising from North Africa and the Middle East? How many people live immersed in violence and endure situations of injustice and persecution! Here I am thinking of the many Christians who are frequently forced to leave their homelands or dwell in them without recognition of their rights, and not enjoying full citizenship. Please, let us commit ourselves so that all who are part of society can become citizens with full rights. Finally, there is a cry of pain that resonates most of all, and it is turning the Mediterranean, the mare nostrum, from the cradle of civilization into the mare mortuum, the graveyard of dignity: it is the stifled cry of migrant brothers and sisters. I want to devote attention to this cry by reflecting on the second image Marseille offers us, that of its port.

2. The port of Marseille has been a wide-open gateway to the sea, to France, and to Europe for centuries. From here many have left to find work and a future abroad, and from here many have passed through the gateway to the continent with luggage laden with hope. Marseille has a large port and is a grand gateway, which cannot be closed. Several Mediterranean ports, on the other hand, have closed. And there were two words that resounded, fueling people’s fears: “invasion” and “emergency.” Thus they closed the ports. Yet those who risk their lives at sea do not invade, they look for welcome, they are looking for life. As for the emergency, the phenomenon of migration is not so much a short-term urgency, always good for fueling alarmist propaganda, but a reality of our times, a process that involves three continents around the Mediterranean and that must be governed with wise foresight, including a European response capable of coping with the objective difficulties. I am looking here, on this map, at the ports preferred by migrants: Cyprus, Greece, Malta, Italy, and Spain... They face the Mediterranean and receive migrants. The mare nostrum cries out for justice, with its shores that, on the one hand, exude affluence, consumerism, and waste, while on the other there is poverty and instability. Here also the Mediterranean mirrors the world, with the South turning to the North, with many developing countries, plagued by instability, regimes, wars, and desertification, looking to those that are well-off, in a globalized world in which we are all connected, but one in which the disparities have never been so wide. Yet, this situation is not a novelty of recent years, and this Pope who came from the other side of the world is not the first to warn of it with urgency and concern. The Church has been speaking about it in heartfelt tones for more than fifty years.

Shortly after the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council, Saint Paul VI, in his Encyclical Populorum Progressio, wrote: “The hungry nations of the world cry out to the peoples blessed with abundance. And the Church, cut to the quick by this cry, asks each and every man to hear his brother’s plea and answer it lovingly” (#3). Pope Paul listed “three duties” of the more developed nations, “stemming from the human and supernatural brotherhood of man… mutual solidarity – the aid that the richer nations must give to developing nations; social justice – the rectification of trade relations between strong and weak nations; universal charity – the effort to build a more human world community, where all can give and receive, and where the progress of some is not bought at the expense of others” (#44). In 1967, in the light of the Gospel and of these considerations, Paul VI stressed the “duty of giving foreigners a hospitable reception,” a duty on which, he wrote, “we cannot insist too much” (#67). Fifteen years earlier, Pope Pius XII had encouraged this, writing that “the Holy Family in exile, Jesus, Mary and Joseph emigrating to Egypt… is the model, example and support for all emigrants and pilgrims of every time and country, and of all refugees of whatever condition who, whether compelled by persecution or by want, are forced to leave their native land and beloved parents… and to seek a foreign soil” (Apostolic Constitution Exsul Familia: de spirituali emigrantium cura, 1 August 1952).

Certainly, no one can fail to see the difficulties involved in offering welcome. Migrants must be welcomed, protected or accompanied, promoted, and integrated. If this does not take place then migrants end up on the margins of society. Welcomed, accompanied, promoted, and integrated: this is the style. It is true that it is not easy to have this style or to integrate unexpected persons, yet the principal criterion cannot be the preservation of one’s own well-being, but rather the safeguarding of human dignity. Those who take refuge in our midst should not be viewed as a heavy burden to be borne: if we consider them instead as brothers and sisters, they will appear to us above all as gifts. Tomorrow we celebrate the World Day of Migrants and Refugees. May we let ourselves be moved by the stories of so many of our unfortunate brothers and sisters who have the right both to emigrate and not to emigrate, and not become closed in indifference. History is challenging us to make a leap of conscience in order to prevent the shipwreck of civilization. For the future will not lie in being closed, which is a return to the past, a turnaround in the journey of history. In the face of the terrible scourge of the exploitation of human beings, the solution is not to reject but to ensure, according to the possibilities of each, an ample number of legal and regular entrances. This would be sustainable with an equitable welcome on the part of the European continent, in the context of cooperation with the countries of origin. Whereas, merely crying “enough!” is to close our eyes; attempting now to “save ourselves” will turn into tragedy tomorrow. Future generations will thank us if we were able to create the conditions for a necessary integration. Otherwise, they will censure us if we favour only sterile forms of assimilation. Integration of migrants is a tiring effort but farsighted; an assimilation that does not take into account differences and remains rigidly fixed in its own paradigms only makes ideas prevail over reality and jeopardizes the future, increasing distances and provoking ghettoization, which in turn sparks hostility and forms of intolerance. We need fraternity as much as we need bread. The very word “brother” in its Indo-European etymology derives from a root associated with nutrition and sustenance. We will support ourselves only by nourishing with hope the most vulnerable, accepting them as brothers and sisters. “Do not neglect to show hospitality” (Hebrews 13:2), Scripture tells us. And in the Old Testament it is repeated: the widow, the orphan, and the stranger. The three duties of charity: assist the widow, assist the orphan, and assist the stranger, the migrant.

In this regard, the port of Marseille is also a “door of faith.” According to tradition, it was here that Saints Martha, Mary, and Lazarus landed and then sowed the seed of the Gospel in these lands. Faith comes from the sea, as we are reminded by the evocative Marseille tradition of Candlemas and its maritime procession. In the Gospel, Lazarus is Jesus’ friend, but also the name of the protagonist of one of his most timely parables, one that opens our eyes to the inequality that corrodes fraternity and speaks to us of the Lord’s preference for the poor. As Christians, who believe in God made man, in the one inimitable Man who on the shores of the Mediterranean called himself the way, the truth, and the life (cf. John 14:6), we cannot accept that the paths of encounter should be closed. Please, let us not close the paths of encounter! We cannot accept that the truth of Mammon should prevail over human dignity, that life should turn into death! The Church proclaims that God in Jesus Christ “in a certain way united himself to every man and woman” (Gaudium et Spes #22) and believes, with Saint John Paul II, that humanity is her way (cf. Encyclical Letter Redemptor Hominis #14). Worship God and serve the most vulnerable, who are his treasures. Adore God and serve your neighbour, that is what counts: not social importance or vast numbers, but fidelity to the Lord and to humanity!

This is Christian witness, and frequently it is even heroic: I think for example of Saint Charles de Foucauld, the “universal brother,” of the martyrs of Algeria, but also of all those agents of charity in our own day. In this scandalously evangelical style of life, the Church discovers the sure port in which to dock and from which to set out in order to weave bonds with the people of every nation, seeking everywhere the traces of the Spirit and offering all that she herself has received by grace. This is the purest reality of the Church, this is – as Bernanos wrote – “the Church of the saints,” adding that “this great apparatus of wisdom, strength, elastic discipline, magnificence and majesty, is nothing by itself, unless inspired by charity” (Jeanne, relapse et sainte, Paris, 1994, 74). I am happy to celebrate this particularly French insight, this creative Christian genius that has reaffirmed so many truths through a multitude of actions and writings. Saint Caesarius of Arles said: “If you have charity, you have God; and if you have God, what do you lack?” (Sermo 22, 2). Pascal recognized that “the sole object of Scripture is charity” (Pensées, No. 301) and that “truth apart from charity is not God but his image and an idol that one must not love or adore” (ibid., No. 767). Hence Saint John Cassian, who died here, wrote that “Everything, even what we consider useful and necessary, is of less value than that good which is peace and charity” (Collationes, XVI, 6).

It is right, then, that Christians should be second to none in charity; and that the Gospel of charity be the magna carta of all pastoral work. We are not called to grieve over times past, or to redefine the Church’s role in society; we are called to bear witness, not to embroider the Gospel with words, but to give it flesh; not to worry about our visibility but to spend ourselves in utter gratuity, believing that “the measure of Jesus is love without measure” (Homily, 23 February 2020). Saint Paul, the apostle of the nations, who spent much of his life crossing the Mediterranean from one port to another, taught that in order to fulfill the law of Christ it is necessary to bear one another’s burdens (cf. Galatians 6:2). Dear brother Bishops, let us not burden others, but relieve their burdens in the name of the Gospel of mercy, in order to spread joyfully the consolation of Jesus to a weary and wounded humanity. May the Church not be a list of regulations but a port of hope for those who have lost their confidence. Please, open wide your hearts! May the Church be a port of refreshment, where people feel encouraged to embark upon life with the incomparable strength born of Christian joy. May the Church not be a customs house. Let us remember what the Lord has told us: everyone, everyone, everyone is invited.

3. I now come, briefly, to my last image, that of the lighthouse, which sheds its beam upon the sea and enables the port to be seen. What luminous beacons of light can guide the route of the Mediterranean Churches? Thinking of the sea, which unites so many different believing communities, I believe that one can reflect on more cooperative ways forward, perhaps considering also the expediency of a Mediterranean ecclesial conference, as Cardinal Aveline mentioned, that could offer greater possibilities for regional dialogue and representation. Also, thinking of ports and the theme of migration, it could be profitable to work towards a specific pastoral plan that is even more interconnected, so that those dioceses that are most exposed can provide the best spiritual and human assistance to our sisters and brothers who arrive there in great need.

Finally, the lighthouse, in this prestigious palace that bears its name, makes me think especially of young people. They are the light that indicates the way of the future. Marseille is a great university city, home to four campuses; of its 35,000 students, 5,000 are foreigners. Where do we start to weave relationships between cultures, if not from the universities? There, young people are not attracted by the seductions of power, but by the dream of building the future. May the Mediterranean universities be laboratories of dreams and workshops of the future, where young people mature by encountering one another, coming to know one another, and discovering cultures and contexts both near and diverse. In this way, prejudices are dismantled, wounds are healed and fundamentalist rhetoric is rejected. Be aware of the preaching of so many fundamentalisms that are fashionable today! Young people, well prepared and used to socializing will be able to open unexpected doors of dialogue. If we want them to devote themselves to the Gospel and the lofty service of politics, we first need to be credible: forgetful of ourselves, free from self-referentiality, dedicated to spending ourselves tirelessly for others. Yet the primary challenge of education has to do with every age level: starting with children, by “mixing” with others, they can surmount barriers, overcome preconceptions, and develop their own identity in a context of mutual enrichment. The Church can certainly contribute to this by offering her educational networks and encouraging a “creativity of fraternity.”

Brothers and sisters, the challenge is also one of a Mediterranean theology – theology must be rooted in life, a laboratory theology does not work – capable of developing ways of thinking rooted in reality, a “home” to human and not only technical data, poised to unite generations by linking memory and future, and promoting with originality the ecumenical journey of Christians and dialogue between believers of different religions. It can be exciting to set out on this adventurous quest, both philosophical and theological, which, by drawing from the Mediterranean cultural sources, can restore hope to men and women, a mystery of freedom, in need of God and others in order to give meaning to their lives. It is likewise necessary to reflect on the mystery of God, whom no one can claim to possess or control, and who must instead be preserved from all violent and instrumental misuse, in the awareness that the confession of his grandeur demands of us the humility of seekers.

Dear brothers and sisters, I am happy to be here in Marseilles! The President had invited me to visit France, but he said: “It is important that you come to Marseilles!” So I have! I thank you for your patience in listening to me and for all your efforts. Continue your courageous good work! Be a sea of good, in order to confront the poverty of today in solidarity and cooperation; be a welcoming port, in order to embrace all those who seek a better future; be a lighthouse of peace, in order to pierce, through the culture of encounter, the dark abysses of violence and war. Thank you very much!

Related Articles:

<<