Baptism in Ecumenical Dialogue: Questions about the Trinitarian Formula | One Body

Sr. Donna Geernaert, SC

Friday, April 12, 2024

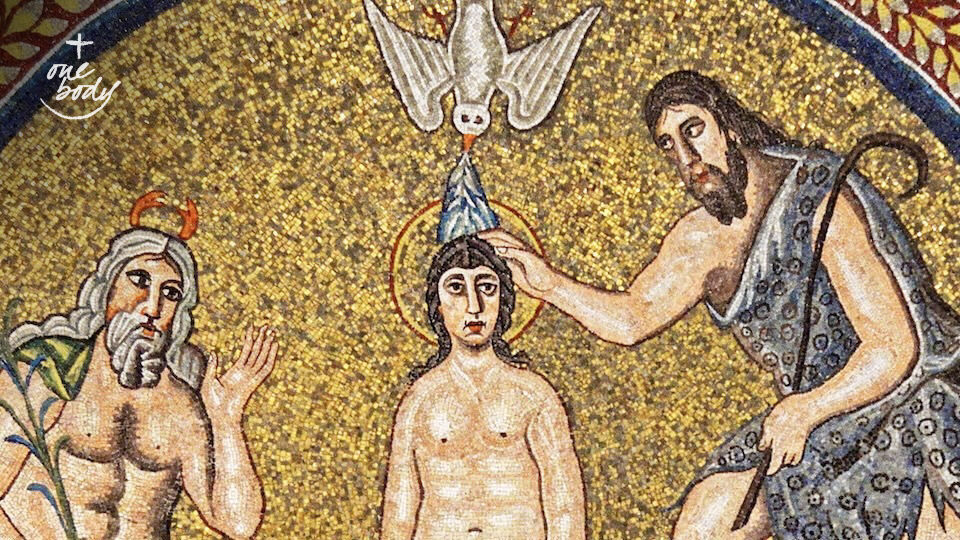

Baptism of Christ, Arian Baptistry in Ravenna. Wikimedia Commons.

Baptism in Ecumenical Dialogue: Questions about the Trinitarian Formula

by Sr. Donna Geernaert, SC

With our recent celebration of the Easter Vigil in mind, it’s a good time to reflect on the ecumenical significance of baptism and offer a brief review of some of the dialogues that have taken place on this topic. From a Catholic perspective, the ecumenical significance of baptism is clearly affirmed in Vatican II’s Decree on Ecumenism, which states that: “all who have been justified by faith in baptism are incorporated into Christ; they therefore have a right to be called Christians, and with good reason are accepted as brothers [and sisters] by the children of the Catholic Church” (#3). Initially developed in the 1967 Directory Concerning Ecumenical Matters, implications of this statement are re-stated in the 1993 Directory for the Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism, which includes a section on validity of baptisms. It asserts: “Baptism by immersion, or by pouring, together with the Trinitarian formula is, of itself, valid.” The minister’s insufficient faith “never makes baptism invalid ... unless there is serious ground for doubting that the minister intended to do what the Church does” (#95). While churches are encouraged to enter into dialogue in order to “arrive at common statements through which they express mutual recognition of baptisms,” the absence of a formal agreement “should not automatically lead to doubt about the validity of baptism” (#94, 99). If careful investigation indicates the need for conditional baptism, “the Catholic minister should show proper regard for the doctrine that baptism may be conferred only once,” and explain why a conditional baptism is necessary. Also, “conditional baptism is to be carried out in private and not in public” (#99). The ongoing ecumenical significance of baptism in Catholic thought is evident in the current Synod on Synodality (see the Synthesis Report 2023, ch. 7), where our common baptismal calling is a key theme in the discussions, particularly about vocation (ch. 3 and 14), orders (ch. 11-12), and the role of women (ch. 9). A 2001 report of the Roman Catholic-United Church Dialogue of Canada offers a concise summary of the first stage of addressing the question in this country:In 1969, the Joint Working Group (JWG) of the Canadian Council of Churches (CCC) and the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB) received a request for an ecumenical study of baptism. The request was forwarded to the CCC’s Faith and Order Commission, which reported to the JWG on the results of its study in May 1972. In its discussion of the topic on September 12, 1972, the JWG decided not to ask the churches to endorse the Report but to receive it “as documentation for a recommendation of mutual acceptance of baptisms.” The JWG formulated two recommendations which were forwarded to the churches on October 31, 1972: 1) that in the absence of evidence to the contrary they accept the validity of baptisms conferred with water, by pouring, sprinkling or immersion, accompanied by the Trinitarian formula; 2) that the churches adopt in addition to whatever certificate or certificates they now use, a common certificate to be agreed upon. (Roman Catholic-United Church Dialogue of Canada, In Whose Name? The Baptismal Formula in Contemporary Culture, Appendix D.)The CCCB’s December,1975 National Bulletin on Liturgy notes that in response to the 1972 JWG Report, Anglican, Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Presbyterian and United churches agreed that any one church would “recognize the validity of baptisms conferred according to the established norms of other churches.” Discussion on the question of a common baptismal certificate continued, but agreement couldn’t be reached and in 1980 that matter was dropped. With the publication of the WCC’s Faith and Order study paper on Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry (BEM) in 1982, ecumenical dialogue on baptism was given new impetus. As many Canadian churches were considering their responses to BEM, the CCC’s Faith and Order Commission held a consultation in 1985 on the pastoral and practical implications of recognizing in that document an expression of “the faith of the church through the ages.” Among its recommendations was the suggestion that, given the agreement already achieved on the meaning and practice of baptism, a common catechesis might be developed. Following the consultation’s recommendation, Commission members began their conversation in the spring of 1986. Consistent with the relationship between worship and belief expressed in the ancient Christian principle of lex orandi, lex credendi, the group agreed to base its study on the actual liturgical practice of its members: Anglican, Baptist, Disciples of Christ, Lutheran, Orthodox, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic, and United churches. Results of the dialogue were published in 1992 under the title of Initiation into Christ: Ecumenical Reflections and Common Teaching on Baptism. The text marks an advance in reception of the ecumenical study of baptism in Canada. It was able to include a number of new participants: Coptic, Greek and Ukrainian Orthodox, as well as Mennonites, Salvation Army, and Society of Friends. Baptists – most of whom firmly believe in adult baptism as a profession of faith – had felt marginalized in the earlier discussion but were now fully involved in the development of this 1992 document. In addition, the text is oriented towards use as a resource for ecumenical dialogue and study in a variety of different settings. While there is much to celebrate in the Canadian churches’ efforts to promote the ecumenical reception of BEM, the possibility of new divisions arising out of contemporary concerns illustrates the fragility of what has been achieved. In particular, the CCCB’s Episcopal Commission for Ecumenism received reports of divergent practice in the use of the trinitarian formula among members of some of the churches who had been party to the earlier agreement on mutual recognition of baptisms. Brought to the attention of the CCC’s Commission on Faith and Witness (CFW) in the spring of 1995, members of the CFW agreed to survey the position and practice in their respective churches. In the spring of 1996, the commission reviewed the results of the survey and found no departure of any significance to the use of the Trinitarian formula (“I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit”) as stated in the earlier CCC agreement. In May 1996, the CCC Governing Board reviewed the Commission’s findings and agreed to forward them to the CCC’s member churches. Bilateral dialogues have the advantage of being able to focus on concerns specific to the sponsoring churches, and in response to a proposal from the United Church’s Inter-Church and Inter-Faith Relations Committee, the Roman Catholic–United Church Dialogue of Canada agreed to look at the use of the Trinitarian formula in the baptismal liturgy. The dialogue began in October 1995 and took place over nine sessions, probing various aspects of the question and attempting “to spell out with clarity what might be gained and what might be put at risk if the United Church, or any other Christian community, were to give official approval to alternative baptismal formulae.” After an initial “review of the development of the doctrine of the Trinity, and a summary of questions raised in feminist discussion of this doctrine,” participants gave careful thought to “what’s at stake in Trinitarian belief and language.” Taking account of personal experience as well as biblical, historical and theological positions, the group considered some criteria for proposing or recognizing alternative baptismal formulae, offered options for an ecumenically sensitive response to feminist concerns, and made recommendations specific to each of the sponsoring churches. A final editing of the report took place in November 1999 and the text, In Whose Name? The Baptismal Formula in Contemporary Culture, was published electronically in 2001. It included a brief study guide and an invitation to members of the two churches, as well as ecumenical partners and theological colleagues to join the dialogue.

Baptism and renewed interest in Trinitarian theology

Biblical evidence for early use of the Trinitarian formula in baptism is found in Matthew’s Gospel (28: 19), the composition of which is usually dated to about 95 CE. Like the followers of many other faith traditions, Christians maintain that God is mystery, beyond all human words and knowing. Yet, Christians also believe their encounter with God in the person of Jesus and the activity of the Holy Spirit has given them a special revelation about who God is. This experience is expressed in a Trinitarian monotheism, maintaining on the one hand, the oneness of God, as well as the divinity and full equality of the divine persons, and on the other hand, their mutual distinction from one another. From the initial debate on the oneness of Father and Son at the Council of Nicaea, later Councils have clarified the concept of Trinitarian Persons distinguished from one another through mutual inter-relatedness. This is well expressed at the Council of Florence (1441-1449) which affirms in God everything is one except for the relative opposition of the persons (Denzinger #1330). In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in Trinitarian theology. Based on the idea of mutual indwelling in the Gospel of John (14:18-23, 15:4, 17:21) and the theme of perich?r?sis, or “coinherence” in the thought of John Damascene (675-721 CE), several theologians (e.g., Denis Edwards, Elizabeth Johnson, Catherine LaCugna, Richard Rohr) have reflected on the concept of relationship as central to the Christian understanding of a God who is Trinity. Further, more than mere speculation on the inner life of God, these theologians claim that it is an eminently practical doctrine, “one that has liberating implications for an understanding of the human person as a being-in-relationships, of creation as springing from divine communion, and of the church as a living sign of this divine communion.” (Denis Edwards, Ecology at the Heart of Faith, New York: Orbis Books, 2006, p. 74) Elements of these recent theological reflections could be helpful in developing a contemporary catechesis on the use of the Trinitarian formula in baptism. More recently, a study document on Ecclesiological and Ecumenical Implications of Baptism produced by the Joint Working Group between the Roman Catholic Church and the World Council of Churches in 2004 offers a comprehensive review of the growing convergence on a common understanding of baptism in the modern ecumenical movement. At the same time, the document recognizes that there still are important issues that need to be resolved before a genuinely common understanding of baptism can be affirmed. In addition, the text refers to the emergence of some new problems which will need to be addressed, lest the convergence and consensus achieved be somehow diminished. Among a list of eleven implications that the study paper draws from the growing ecumenical convergence on baptism, it is interesting to note that three of these have been on the agenda of Canadian dialogue groups: statements of mutual recognition (#103), development of an ecumenical catechesis (#104), use of Trinitarian language (#109). Sr. Dr. Donna Geernaert, SC, served for 18 years in promoting ecumenical and interfaith relations for the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. She has been a staff member, consultant, and member of numerous multilateral and bilateral theological dialogues in Canada as well as internationally.

Sr. Dr. Donna Geernaert, SC, served for 18 years in promoting ecumenical and interfaith relations for the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. She has been a staff member, consultant, and member of numerous multilateral and bilateral theological dialogues in Canada as well as internationally.

Related Articles:

<<